A few weeks ago a group of us felt it was critical to put together a Manifesto for Open Content Mining. We wanted people who understood the issues, were clear thinkers, balanced outlook and committed to making solid, rapid progress. Among those who come immediately to mind is Richard Poynder who runs the GOAL OA mailing list and also a very thoughtful blog. It’s on the latter that he has written up the current state of play.

I’m going to quote from it, and then add some comments on the current state of content-mining. As always you should read Richard’s blogs in full (http://poynder.blogspot.co.uk/2012/06/new-declaration-of-rights-open-content.html ) .

In a recent investment report, analyst Claudio Aspesi concluded that a new front had opened up in the Open Access (OA) debate. Writing in April, Aspesi noted that academics are “increasingly protesting the limitations to the usage of the information and data contained in the articles published through subscription models, and — in particular — to the practice of text mining articles.” Aspesi is right, and a central figure in this battleground is University of Cambridge chemist Peter Murray-Rust. A long-time advocate for open data, Murray-Rust is now spearheading an initiative to draft a “Content Mining Declaration“. What is the background to this?

Let’s be clear. Content mining is now centre stage. Everyone has to take a position or be sidelined. He describes my efforts over the years…

What Murray-Rust wanted to do, he explained, was to capture the “embedded data” contained in the tables, charts, and images published in science papers, along with the “supplemental information” that often accompanies papers. To do this, he had developed a variety of software tools to mine large quantities of digital text. Having extracted the data he then wanted to aggregate them, compare them, input them into programs, use them to create predictive models, and reuse them in a variety of other ways.

However, he was having huge problems achieving this, not because of any technical issue, but because of uncertainty over copyright and publishers’ insistence that a licence to read journals does not encompass the right to mine them with software.

The key point. It’s not a technology problem. It’s 100% in the hands of the publishers.

We use the term “Content mining” since…

Simply using the term “text mining”, [PMR] adds, “might imply that anything other than text should be protected by the ‘content provider’. However, I and others can extract factual information from a wide range of material.”

It’s down to policy:

First, there is a growing acceptance that traditional IPR is impeding or preventing a good deal of innovation in today’s digital environment. This has made governments more open to the suggestion that it may be necessary to recalibrate copyright for the networked world.

In November 2010, for instance, the UK Prime Minister David Cameron commissioned Professor Ian Hargreaves to review the current situation. This led to the publication in May of last year of a report — Digital Opportunity: A Review of Intellectual Property and Growth — in which 10 major changes to the current intellectual property regime were proposed, including changes to copyright laws that Hargreaves concluded “obstruct innovation and economic growth in the UK”. If these are all implemented, The Guardian suggested last year, it will amount to an “overhaul of copyright laws” in the UK.

…

In short, concluded Hargreaves, “Text mining is one current example of a new technology which copyright should not inhibit, but does. It appears that the current non-commercial research ‘Fair Dealing’ exception in UK law will not cover use of these tools under the current interpretation of ‘Fair Dealing’. In any event text mining of databases is often excluded by the contract for accessing the database.”

For this reason, said Hargreaves, “any new text mining exception [would also need to] include provision to override any attempt to set it aside in the words of a contract.”

On 14th March, for instance, the UK’s Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) published a report on text mining. This listed a number of benefits that text mining could be expected to provide, including, “increased researcher efficiency; unlocking hidden information and developing new knowledge; exploring new horizons; improved research and evidence base; and improving the research process and quality. Broader economic and societal benefits include cost savings and productivity gains, innovative new service development, new business models and new medical treatments.”

Unsurprisingly, JISC concluded by reiterating Hargreaves call for a text mining exception.

I’m missing out whole chunks of worthwhile stuff from Richard… But here’s another crunch point.

Writing on 7th March, Nature summed up the current situation in this way: “Publishers point out that they receive few text-mining requests, so the field can’t be very hot. So unless text-miners start to make full use of the content that is available, and request more access to published content — while always being clear about how their project will benefit science — the unsatisfactory impasse will continue.”

The JISC report, however, concluded that text mining is currently rare not because there is a lack of interest in doing so, but because publishers take an overly proprietorial attitude to the papers they publish. “[T]ext mining is currently extremely limited within UKFHE,” the report noted, “in part at least due to the current licensing arrangements. A text mining exception, if it were to be implemented, would remove a key barrier thus better enabling service solutions supporting text mining to emerge from the market.”

I’ll reinforce this with our own data later. Here’s part of the publishers’ response:

We noted Taylor’s claim that publishers are happy to allow researchers to text mine. Wiley-Blackwell’s Bob Campbell has made the same claim. In an email to Murray-Rust in March, Campbell said, “[A]nyone interested in mining our journal content should contact us. Any such inquiries will be treated on a case-by-case basis.”

Indeed, publishers get rather hot under the collar when they are told that they are withholding permission from researchers who want to text mine their journals. Responding to an article on text mining in The Guardian, for instance, Taylor wrote, “To say that text mining is ‘forbidden’ and ‘prevented’ by publishers is as we have grown to expect from The Guardian a tendentious and limited analysis.”

I’ll deal with this later.

When I asked Murray-Rust if he concurred with Wise that Elsevier had as good as agreed conditions for him to text mine its journals, he replied. “I don’t want to use Elsevier’s API. That means 100 APIs for me to learn — one per publisher.”

The nub of the issue, it seems is that researchers resent publishers’ proprietorial approach, and are thus reluctant to comply with publisher-dictated rules. “In fact, I only need a single API — a DOI resolver,” Murray-Rust told me. “I may wish to systematically mine a single publisher — in which case I use a list of their DOIs, or I may want to follow links — that’s exactly the same process. Yes I need an API per publisher but I and others are hacking this and it’s a one-off. So a publisher API makes it worse.”

And this

Richard goes on to describe why I – and others – feel that most current approaches to Open Access don’t hep in freeing up access to textmining:

As we noted earlier, however, the OA movement has not pursued reuse rights nearly as vigorously as it might have. Even today many OA publishers still do not use CC-BY licences. Indeed, OA advocate Peter Suber estimates that 88% of OA journals still do not do so.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, in 2010 only 41% of the OA content in UKPMC (the UK version of PubMed Central) was free to read and to reuse (although this is up from 30% in 2009 and 7% in 2001). More depressing for text miners, Suber estimates that the portion of PubMed Central itself that offer reuse rights is only 18.75% —

[Peter Suber is also a member of our manifesto group].

Richard goes on to describe how Heather Piwowar, UBC and Elsevier negotiated an ad hominem agreement for HP to mine the Elsevier literature for her current project. [I reiterate – you should read Richard’s blog post in full].

However it was immediately clear to Piwowar’s text-mining colleagues that the method utilised by Elsevier simply would not scale. Six publishers, a librarian, and a researcher all devoting a large chunk of their time to come to a single agreement, they argued, makes no sense whatsoever.

There was also a sense that Piwowar had been slightly railroaded by Elsevier. Murray-Rust made these points at the time on Piwowar’s blog. “By dealing with Elsevier you have implicitly agreed that Elsevier has the right to control what you do. That they will then generously allow you a subset of the rights that they currently deny us. If all universities follow the course of UBC we shall end up in a situation where Elsevier’s walled garden philosophy controls all of us. We have a fundamental right to text-mine the literature. This agreement has given that up. I am sure it was well intentioned but that’s the effect.”

For all that, Piwowar attracted a lot of publicity for the text mining cause. So too have the activities of Murray-Rust, Max Haeussler and Casey Bergman (the latter two run the text2genome project together); and as the expectations of text-miners repeatedly bump up against the constraints imposed by publishers, so a growing number of incidents can be expected to attract further publicity, and consequently more mindshare, for text mining.

And so – for me – little progress…

Nature aside perhaps, publishers appear to take the view that text mining should not be viewed as an automatic right for subscribers, and while some publishers now evidently accept that text mining should be countenanced, they maintain that the right to do so is separate to the right to read, and so must be negotiated on a case-by-case basis (preferably with the institutional library rather than with researchers themselves). Others remain unwilling even to contemplate it (or will only permit it on payment of an additional fee — again, on a case-by-case basis).”

But there does seem to be movement. For instance, publishers can clearly see that agreeing text-mining rights on a case-by-case basis simply cannot scale. For that reason, Taylor explained in The Guardian, they are “looking into model licences, a clearing house for permissions, a collective licence to support the ‘smaller’ publishers, a guide for those short on ‘understanding”, even a mine itself through CrossRef.”

But little of this may prove acceptable to researchers, not least because they believe it is too late for publishers to start making gestures and offering concessions and expect researchers to allow them to dictate the terms. They have become too angry, and too alienated. Above all, they do not accept that publishers have the right to dictate the terms and conditions for accessing content to which their institution has already paid a licensing fee.

That’s my worry. That the publishers will come up with agreements – unlilaterally – and then pressure universities (mainly through their librarians) to sign them. I say “pressure” because virtually no library has ever successfully challenged the terms that publishers require them to sign. If they had stood up for scholars’ rights we wouldn’t be in this awful position.

That’s why we are creating this Manifesto. To stop even more of our rights being given up.

It’s still a work in progress. But we have a draft. I’ll summarise as:

P M-R: The aim is to do the following:

And Our base claim is that the

right to read is the right to mine.

So – and it’s been a long post. I’ll summarise MY current position.

Biomed Central. NO PROBLEM. I mine this every day. Because it’s CC-BY I don’t have to ask. I haven’t crashed the BMC server and I never will. That’s a super-FUD argument dreamt up by the publisher lobby.

PLoS. NO PROBLEM. Same as BMC.

THERE IS NOT TECHNICAL PROBLEM IN CONTENT-MINING. WE DON’T NEED AN API FROM EACH PUBLISHER. ROSS MOUNCE HAS THE WHOLE OF PLOS ON HIS MACHINE. THAT DOESN’T CRASH ANYONE.

That’s the positives. Now my 6 requests, made in public. I was asking for permission to mine the content they sell me (rent me) for my research. I was not asking for permission to have an extended series of emails. I was not asking for permission to skype them. I was not asking permission to meet with them and my librarians.

I was asking for permission to mine the content.

I wanted a clear answer.

“YES”.

Not one of the six gave me that simple answer. It was always “in principle”, “let’s meet”, “with some technical adjustments”. That’s why I refute Graham Taylor’s argument that everything is fine except for PMR.

I had extended emails – especially with Elsevier. This has been a total waste of my time. Elsevier pay their staff (from our subscriptions) to go through these rituals. They can afford the time – it’s in their favour. They benefit from not allowing me to mine.

Anyway rather than summarize the replies myself one of my colleagues has done so (I shan’t say whom). They said they had never seen such woolly language and that summarising had been a major pain. But here’s the score – not my words.

* Publishers’ responses [all emails can be made public]

* Elsevier – “We (at Elsevier) have no problem in principle with you text mining for research purposes” but wished to discuss ‘practical matters’ which included using their APIs / tools / methods and liaising through librarians, rather than permitting accessibility via [PMR] own tools.

* Nature – “We allow site licence customers to mine licensed text (for non commercial purposes) subject to contract” which includes non-violation of copyright, low-impact crawler and secure storage, which is straight-forward; but “also only for the purposes of the stated experiment” which is restrictive, as is the NC requirement.

* Springer – “The overall answer is yes Springer does support text mining of our content by users” but noted concerns about “systematic downloading” causing “DNS errors and the performance drag”, assumed NC purposes and said “mining is subject to separate accounts and agreements and reporting in order to keep a clear view on the traffic of the publisher’s site”.

* ACS – “ACS does not grant to you, as an individual investigator, permission to perform large-scale text and data mining across the entire corpus of our publications” but suggested they “engage directly with your library colleagues… to clarify with the Cambridge University library representatives what additional terms and conditions” are required.

* RSC – Agreed in principle but stated “Our concern is if the mining extracts and republishes sufficient content from the publications as to reduce apparent usage (and citation) of the published papers in future” and suggested some untenable practice (including references subject to never-changing URL systems, and ‘Fair Use

provisions’ and ‘copyright terms’ which don’t exist); “in summary, we would strongly appreciate discussion on the extent of the factual information you intend to republish, together with the involvement of your librarian colleagues in the process.”

* Wiley – No clear response (asked for more information and referred to “work on a specific project” – “willing to discuss a license for a pilot TDM project with a subset of our journals in order to establish how best we can enable access to our content for mining purposes… involve the UL… get a better understanding of how you plan on processing content (i.e. what you mean when you say ‘extract all the chemical facts and do research on them’), and in particular how the outputs of that processing will be distributed (i.e. what you mean when you say you want to be able to ‘publish the data on which the science is based’)”).

So can I start text-mining tomorrow?

NO – from six voices.

Just remember it took Heather P months to get an agreement with Elsevier for one project. It’s taken me nearly THREE YEARS of countless emails with Eslevier and got nowhere. “In principle” is effectively saying no.

The central point is:

THE PUBLISHERS MADE THESE RESTRICTIONS AND FORCED THEM ON LIBRARIANS.

THE PUBLISHERS CAN TAKE THEM AWAY.

If they don’t, we’ll fight and keep fighting.

And the world will get very very tired of hearing that publishers are “helping scientists” when they can see that they are stopping them doing anything.

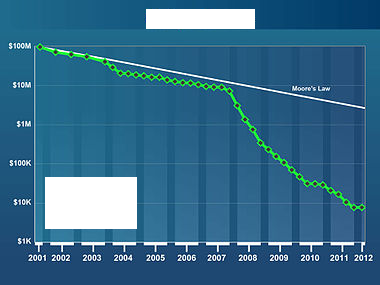

Publishers are losing goodwill and credibility. They should worry that when their walled gardens collapse they will be left with nothing. Even Elsevier shareholders could see that.

And I’ll deal with Elsevier in the next blog.