A FORB (Wikipedia)

A FORB (Wikipedia)

One of the arguments scholarly publishing is that it is for “academics to publish to academics”. Even Open Access advocates such as Stevan Harnad have stated this publicly. I find this arrogant and unacceptable – I think with modern resources such as Wikipedia and Internet search engines much of science is accessible to a huge number #schiolarlypoor. (people outside rich universities with no access to closed publications).

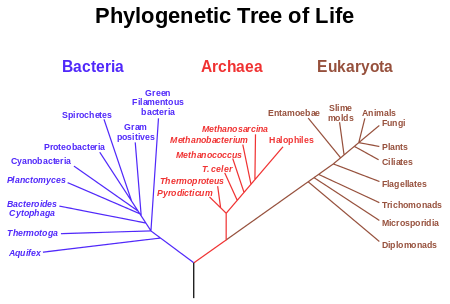

I am trained as a chemist, crystallographer, self-taught computer-scientist and I have no formal biology training. But Ross Mounce and I are working on liberating the world’s phylogenetic trees. DON’T switch off at “phylogenetic” – like many scientific terms you know much about http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phylogenetic_tree already. Can you understand:

A phylogenetic tree or evolutionary tree is a branching diagram or “tree” showing the inferred evolutionary relationships among various biological species or other entities based upon similarities and differences in their physical and/or genetic characteristics. The taxa joined together in the tree are implied to have descended from a common ancestor.

I think anyone with high school education will (or should!) be familiar with everything here. The only difficult words are “entities” (posh word for “thing”) and “taxa” which is either fairly obvious or you can look up. Again from Wikipedia:

A taxon (plural: taxa) is a group of one (or more) populations of organism(s), which a taxonomist adjudges to be a unit. Usually a taxon is given a name and a rank, although neither is a requirement. Defining what belongs or does not belong to such a taxonomic group is done by a taxonomist with the science of taxonomy. It is not uncommon for one taxonomist to disagree with another on what exactly belongs to a taxon, or on what exact criteria should be used for inclusion.

And here is the tree. You may not understand all the names (*I* don’t!) but you can see “Bacteria”, “Animals”, “fungi”, “plants”, etc. I don’t need to understand everything – because I have colleagues such as Ross Mounce and Matthew Wills at Bath I am working with.

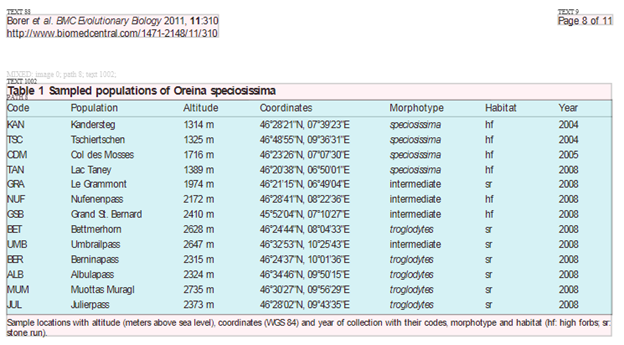

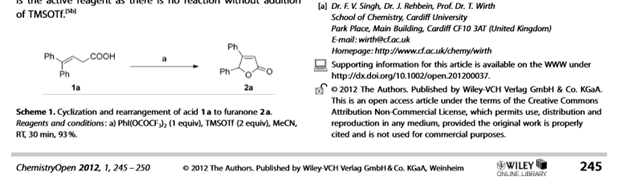

So here is a page of BMC Evolutionary Biology that #AMI2 has turned into HTML. Can you understand it? (It’s a LOT easier than understanding domestic energy tariffs in UK):

From this interaction follows that divergent selection between ecological niches is a major driving force differentiating lineages until reproductive isolation occurs [17]. Ecologically divergent pairs of populations will show higher levels of reproductive incompatibility and lower levels of gene flow than ecologically more similar population pairs [29]. A resulting corollary is that ecological speciation is more likely to arise in regions with patchworks of contrasting habitats and/or distinct environmental gradients.

PMR. Some of the long words are precise terms but I think this could be written in simpler language.

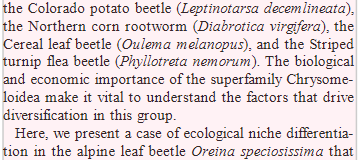

The number of taxa within the insect order Coleoptera exceeds that of any known plant or animal group [30]. More than half of the beetles are phytophagous, including the species rich superfamilies Curculionoidea and Chrysomeloidea, of which a majority feeds on angiosperms [31]. The increase in phytophagous beetle diversity was facilitated by the rise of flowering plants [31]. The family Chrysomelidae currently consists of more than thirty-five thousand recognized species including economically important pest species such as the Colorado potato beetle ( Leptinotarsa decemlineata), the Northern corn rootworm ( Diabrotica virgifera), the Cereal leaf beetle ( Oulema melanopus), and the Striped turnip flea beetle ( Phyllotreta nemorum). The biological and economic importance of the superfamily Chrysomeloidea make it vital to understand the factors that drive diversification in this group.

Here, we present a case of ecological niche differentiation in the alpine leaf beetle Oreina speciosissima that may represent the early stages of ecological speciation. The genus Oreina currently includes twenty-eight species, of which only seven early-diverging taxa do not exclusively occur in high forbs (i.e. five develop in stone run vegetation and two can be found in both high forbs and stone runs) [32]. According to current knowledge [34], the most parsimonious explanation is that high forbs vegetation is the ancestral niche for the remaining twenty-one Oreina lineages, among which only our focal taxon Oreina speciosissima shows a partial reversal, since it is found both in high forbs and stone run vegetation.

Oreina speciosissima is distributed across nearly the entire range of the genus Oreina (from the Pyrenees in the west to the Carpathian Mountains in the east) through a wide altitudinal gradient (ranging from 800 to 2700 m above sea level). At lower elevations it generally colonizes the very abundant high forbs vegetation whereas at higher elevations it is found in stone run habitats across a small portion of its distribution range [unpublished observations MB, TVN][32]. Kippenberg [32] and personal observations suggest that Oreina speciosissima feeds exclusively on Asteraceae ( Achillea, Adenostyles, Cirsium, Doronicum, Petasites, Senecio and Tussilago) and colonizes four distinct habitats

Did you understand it’s about how beetles in European mountains evolve? You may very probably know about European biology (when at school I used to travel to the Alps and identify and photograph alpine plants and to ring (band) birds). That was before I became an “academic”. But I knew all the binomials of European birds and plants I had seen. If you are similar you are entitled to be part of open scholarship.) There are words I don’t know: “forbs”

[“A forb (sometimes spelled phorb) is a herbaceous

flowering plant that is not a graminoid (grasses, sedges and rushes). The term is used in biology and in vegetation ecology, especially in relation to grasslands[1] and understory. From Wikipedia]

And I didn’t know “stone run” either:

A stone run (called also stone river, stone stream or stone sea[1]) is a conspicuous rock landform, result of the erosion of particular rock varieties caused by myriad freezing-thawing cycles taking place in periglacial conditions during the last Ice Age.[2]

But I am sure you understood it!

We have the equipment to open scholarship to the world. Let’s embrace and use it.