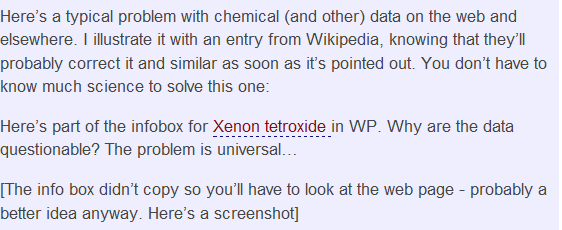

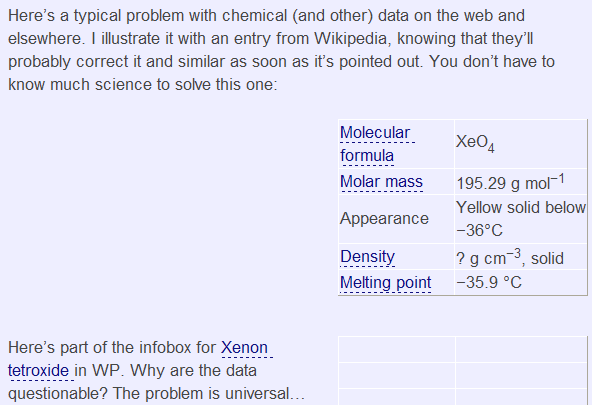

“In the pipeline” is an impressive and much-followed part of the chemical blogosphere. I’m a bit late on its post Kids These Days! which deals in depth with a case (Menger / Christl pyridinium incident) of published scientific error. The case even got as far as Der Spiegel – the German magazine. It’s worth reading (the link will take you to other links and also a very worthwhile set of comments from the blogosphere).

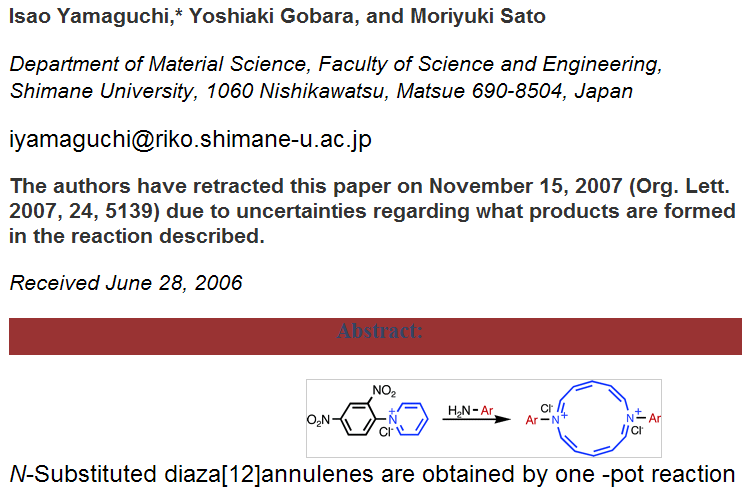

My summary is that: some chemists reported the synthesis of a novel set of compounds, published in Angewandte Chemie (Wiley) (2007) and Organic Letters (ACS) , (2006). After publication, doubt was thrown on the identification of the products, claiming that analytical evidence had been misinterpreted. As a result the original authors withdrew their claim. [The blogosphere has the usual range of opinions – the referees should have picked this up, the authors were sloppy, the criticism was rude, the reaction had been known for 100 years, etc. All perfectly reasonable – this is a fundamental part of science – it must be open to criticism and falsifiability. We expect a range of opinions on acceptable practice.]

What worried me was one comment that the publisher had altered the scientific record.

Metalate on December 1, 2007 11:00 AM writes…

Has anyone noticed that OL has removed all but the first page of the Supporting Info from the 2006 paper? Is this policy on retracted papers? And if so, why?

Permalink to Comment

PMR: I wasn’t reading this story originally, so went back to the article:

As I am currently not in cam.ac.uk I cannot get the paper without paying 25 USD (and I don’t want to take the risk that there is nothing there. I’ll visit in a day or two).

But the ACS DOES allow anyone to read the supporting information for free (whether they can re-use it is unclear and it takes the ACS months to even reply on this). So I thought it would be an idea to see if our NMREye calculations would show that the products were inconsistent with the data. I go to the supporting information

and find:

[On another day I would have criticized the use of hamburger bitmaps to store scientific information but that’s not today’s concern.]

There is only one page. As it ends in mid sentence I am sure Metalate is correct.

The publishers have altered the scientific record

I don’t know what they have done to the fulltext article. Replaced it by dev/null? Or removed all but the title page?

This is the equivalent of going to a library and cutting out pages you don’t agree with. The irony is that there is almost certainly nothing wrong with the supporting information. It should be a factual record of what the authors did and observed. There is no suggestion that they didn’t do the work, make compounds, record their melting points, spectra, etc. All these are potentially valuable scientific data. They may have misinterpreted their result but the work is still part of the scientific record. For all I know (and I can’t because the publisher has censored the data) the compounds they made were actually novel (if uninteresting). Even if they weren’t novel it could be valuable to have additional measurements on them.

I have a perfectly legitimate scholarly quest. I want to see how well chemical data supports the claims made in the literature. We have been doing this with crystallography and other analytical data for several years. It’s hard because most data is thrown away or in PDF but when we can get it the approach works. We contend that if this paper had been made available to high throughput NMR calculation (“robot referees”) – by whatever method – it might have been shown to be false. It’s even possible that the compounds proposed might have been shown to be unstable – I don’t know enough without doing the calculations.

But the publisher’s censorship has prevented me from doing this.

The ACS takes archival seriously: C&EN: Editor’s Page – Socialized Science:

As I’ve [Rudy Baum] written on this page in the past, one important consequence of electronic publishing is to shift primary responsibility for maintaining the archive of STM literature from libraries to publishers. I know that publishers like the American Chemical Society are committed to maintaining the archive of material they publish.

PMR: I am not an archivist but I know some and I don’t know of any who deliberately censor the past. So I have some open questions to the American Chemical Society (and to other publishers who have taken on the self-appointed role of archivist):

- what is the justification for this alteration of the record? Why is the original not still available with an annotation?

- who – apart from the publisher – holds the actual formal record of publications? And how do I get it? (Remember that a University library who subscribes to a journal will probably lose all back issues – unlike paper journals the library has not purchased the articles, only rented them). I assume that some deposit libraries hold copies but I bet it’s not trivial to get this out of the British Library.

- where and how can I get hold of the original supplemental data? And yes, I want it for scientific purposes – to do NMR calculations. Since it was originally free, I assume it is still free.

Surely the appropriate way to tackle this is through versions or annotations? One of the many strengths of Wikipedia is that it has a top-class approach to versions and annotations. If someone writes something that others disagree with, the latter can change it. BUT the original version still exists and can be easily located. If there is still disagreement, then WP may put a stamp of the form “this entry is disputed”. Readers know exactly where they are and they can see the whole history of the dispute.

So here, surely, the simple answer is to preserve, not censor, the scientific record. The work may be “junk science” but it is still reported science. Surely an editor should simply add “The authors have retracted this paper because…” on all documents and otherwise leave them in full.

It is obvious that this problem cannot arise with Open Access CC-BY papers because anyone can make a complete historical record as soon as they are published.

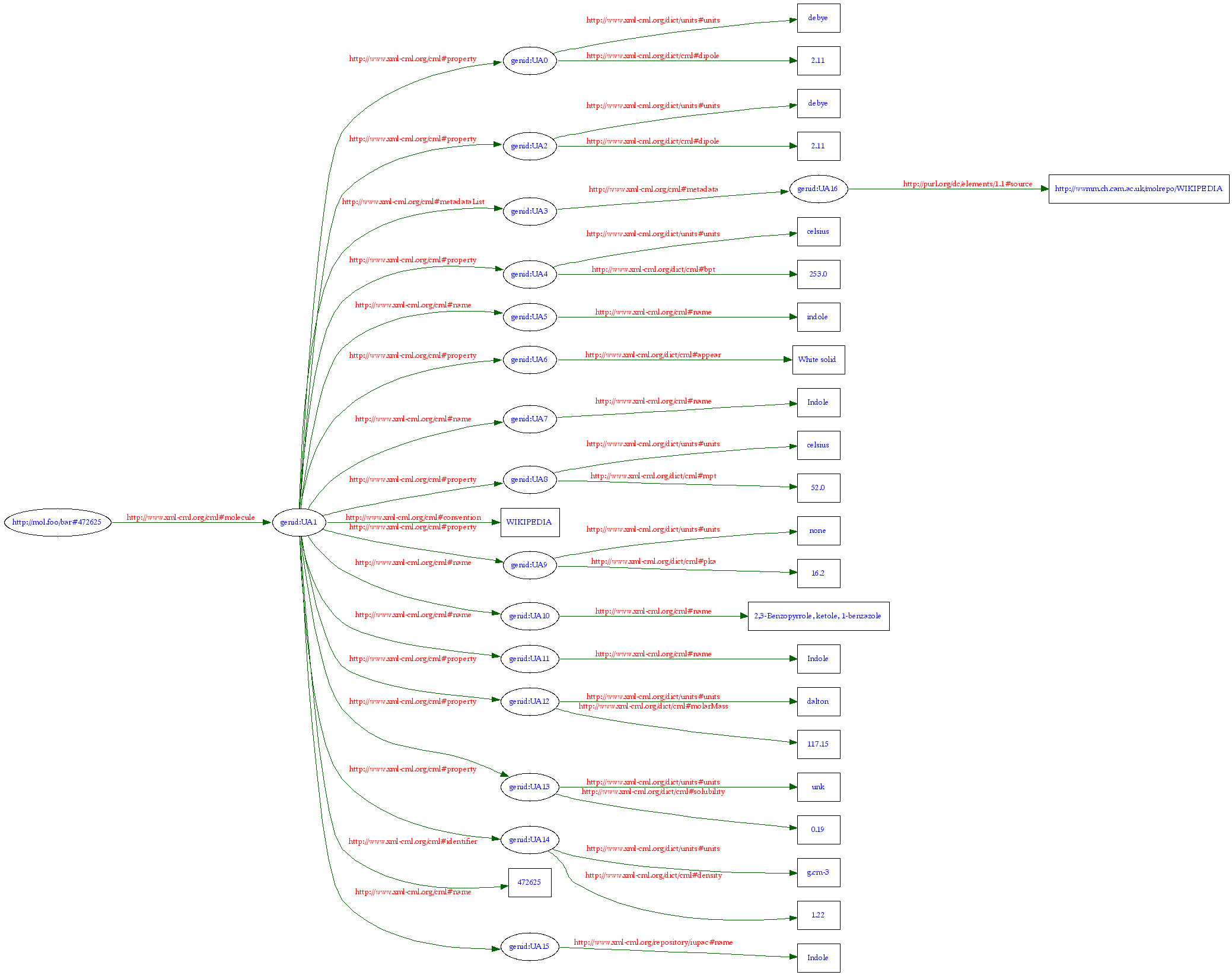

[UPDATE. I have now looked at the original article and this seems to have been treated satisfactorily – the fulltext is still available, with an annotation that “The authors have retracted this paper on November 15, 2007 (Org. Lett. 2007, 24, 5139) due to uncertainties regarding what products are formed in the reaction described.” That’s fair and I have relatively little quibble – although it would still be valuable to see the original and not simply an annotated version.

But the arguments about the supplemental data still persist. If it’s deliberate it’s very worrying. If it’s a technical error in archival it’s also very worrying. ]