Typed and edited into Arcturus

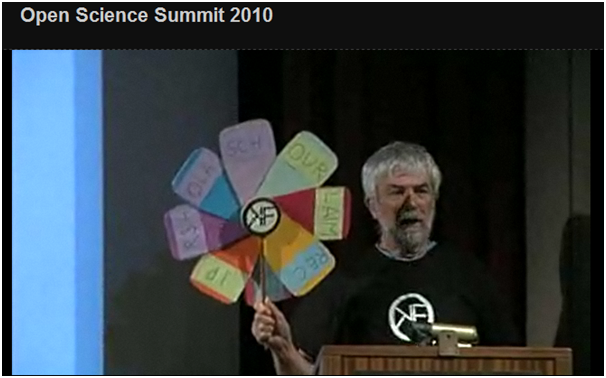

There’s an impressive (near verbatim) transcript of the sessions. this is often at least as useful as the slides. In my case essential. I do not use Powerpoint and instead click my way through my “slides” in a non-linear order according to how I interpret the session and audience.

This time all slides were projected remotely (i.e. there was no podium computer and no VGA connector). So I hurriedly typed a few links into a blog post and asked the projectionist to click on about 2-3. The OK Definition, the picture of the Panton Arms and Pantonistas, The Panton Principles. Most of the talk was done with Flowerpoint. What I said is here:

http://gnusha.org/open-science-summit-2010-transcript.html

and my slight editing (e.g. removing “click here” and correcting names) gives:

I am a chemist. I do not do PowerPoint […] My main method of presentation is flowerpoint. I am old enough to have remembered the 60s and not to have been at Berkeley but it has made a huge contribution to our culture. [describing the flowerpoint] The Open Knowledge Foundation will adopt [flowerpoint] as a way of making my points.

We [OKF] have many different areas- maybe 50- that come under Open, that relate to knowledge in general. First of all, my petals are going to talk about various aspects of Openness. […] the open knowledge definition. This is the most important thing in [my talk and message].

A piece of knowledge is open if you are free to use, re-use and re-distribute it, subject only [possibly] to attribute and share-alike.

That’s a wonderfully powerful algorithm. If you can do that, it’s open. If not, it’s not open according to this [?definition].

Another picture [the Panton Arms with PP collaborators], Panton Principles. It’s a placed called a pub. It’s 200 meters from the chemistry department where I work, and between the pub and the chemistry lab is the Open Knowledge Foundation. Rufus has been successful in to getting people to work on [OKF]. A lot of this is about government, public [knowledge].

[petal 1]How many people have written open source software? [many hands]

[petal 2] What about open access papers? [fewer] How many of them had a full CC-BY license [fewer still]. If they weren’t, they didn’t work as open objects. CC-NC, causes more problems than it solves.

[petal 3] How many people have either published or have people in their group who have published a digital thesis, not many, right? [few hands] How many of those explicitly carry the CC-BY license. [about zero] That’s an area where we have to work. Open Theses are a part of what we’re trying to set up in the Open Knowledge Foundation. Make the semantic [version] available, LaTeX, Word, whatever they wrote it in, that would be enormously helpful. The digital landgrab in theses is starting and we have to stop it. There are many things we can do.

[petal 4 + 5] There are two projects, and these have been funded by JISC. Open Bibliography and Open Citations. At the moment, we’re being governed by non-accountable proprietary organizations who measure our scholarly worth by citations and metrics that they invent because they are easy to manage and retain control of our scholarship. We can reclaim that within a year or two, and gather all of our citation data, and bibliographic data, and we can then, if we want to do metrics, I am not a fan, but we [emphasis] should be doing them, and not some unaccountable body. Anyone can get involved in Open Bibliography and Open Citations.

[petal 6] The next is open data, and the next is very straight forward. Jordan Hatcher, John Wilbanks from Science Commons, have shown that open data is complex. I think it’s going to take 10 years [to get to terms with Open Data].

[petal 7]This is a group involved in the Panton Principles, Jenny Molloy, Jenny is a student. The power of our students.. undergraduates are not held back by fear and conventions. She has done a fantastic job in the Open Knowledge Foundation. [identifies people in photo] Jordan, then Rufus, John Wilbanks, Cameron, and me, and anyway, we came up with the Panton Principles, [link to ] the Panton Principles, and let’s just deal with the first one [due to time and not being able to scroll down].

Data related to public science should be explicitly placed in the public domain.

There are four principles to use when you publish data. What came out of all of this work is that, one should use a license that explicitly puts your [data] in the public domain – CC0, or PDDL from the Open Knowledge Foundation. So, the motto that I have brought to this [meeting] is one which I’ve been using and been taken up by JISC.. … on the reverse of the flower,

reclaim our scholarship.

That’s a very simple idea, one’s that possible if a large enough number of people in the world look to reclaiming scholarship, we can do it. There are many more difficult things that have been done by concerted activists. We can bring back our scholarship where we [emph] control it, and not others.

[petal 8] I would like to thank to people on these projects, Open Citations (David Shotton) and our funders and collaborators who are JISC, who funds it, BioMed Central who also sponsors this, International Union of Crystallography, Public Library of Science. (applause)

Chris Rusbridge says:

Chris Rusbridge says: