For whatever reason I get very few comments on this blog (note: I try to be courteous to posters). Comments normally come when I upset people and overstep a line (“turning up the outrage knob”). I don’t generally do this consciously. Anyway I have got two useful comments on my criticism of the EPSRC Bourne plot (/pmr/2011/09/28/epsrc-will-eventually-have-to-disclose-where-the-bourne-incredulity-comes-from-so-please-do-it-now/ ).

I’ll post the comments and reply:

Jeremy Bentham says: September 28, 2011 at 9:17 am

Jeremy Bentham says: September 28, 2011 at 9:17 am

We need to raise the quality of this debate – I’m not saying EPSRC is right but it doesn’t help by distorting what they are actually saying. Let’s make a bit more effort to understand what EPSRC have done, why they have done it, and start arguing on a basis of accurate information. EPSRC have actually been very open about why they are doing this, what the process has been, and what inputs they used to make strategic decisions.

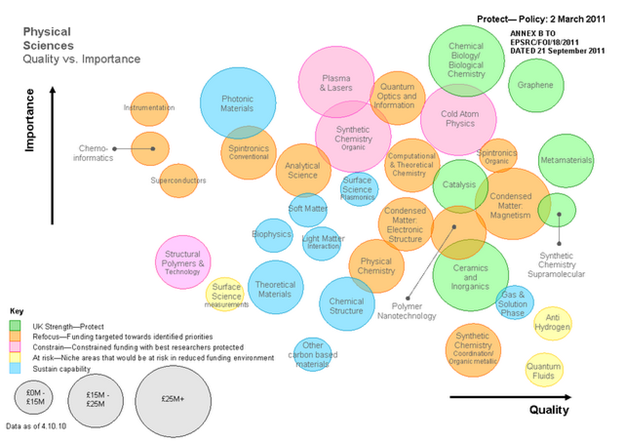

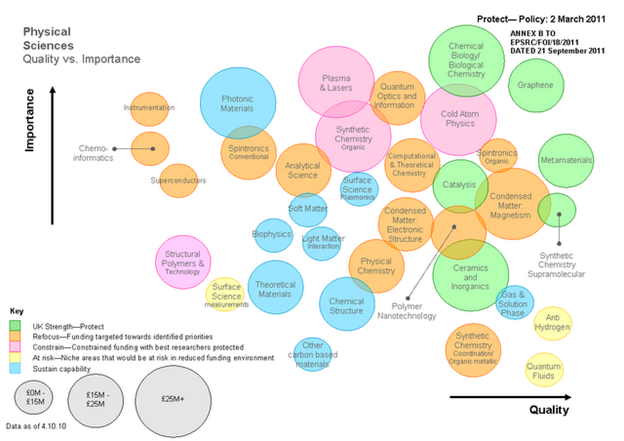

Bourne’s team have actually published quite a detailed explanation on how they made *informed judgements* about the physical sciences portfolio which is represented by the QI plot (just because a diagram isn’t quantifiable doesn’t mean it isn’t representative of something)

Read this and please blog again http://tiny.cc/f66xw

PMR: Thanks Jeremy. I agree that my challenge included discourse that I would not use in a measured response. It may trivialize some issues but it also emphasizes the real sense of injustice and arbitrariness felt by many (not just me). It’s a political, not an analytical, post and perhaps more suited to Prime Minister’s Question Time. I have read many of the chemistry documents you list and will comment. I cannot presently see how those documents translate into the Bourne diagram.

Walter Blackstock says: September 28, 2011 at 12:44 pm

Walter Blackstock says: September 28, 2011 at 12:44 pm

You may be interested in Prof Timothy Gowers’s deconstruction of the EPSRC announcement. http://gowers.wordpress.com/2011/07/26/a-message-from-our-sponsors/

PMR: This is an exceptionally powerful piece. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timothy_Gowers is not only a mathematics superstar but also a star of the blogosphere. He created and catalysed the Polymath project, where a virtual group of mathematicians proved an extremely challenging unsolved conjecture. He is rightly hailed as a prophet of new web-based scholarship and I try to emulate the approach in activities such as Quixote. The piece is deliberately underspoken and he uses the EPSRC language itself as as a weapon against their mathematics policy. (In simple terms this is that only certain areas of maths are worth funding. )

PMR Comments on JB and EPSRC chemistry.

I will reread the documents and see what I may have missed. If there is a clear explanation of how Bourne came to create the diagram then I (and many others) have missed it and would welcome it. Let me take:

http://www.epsrc.ac.uk/SiteCollectionDocuments/Publications/reports/ChemistryIR2009.pdf

in which an invited group of top international chemists analysed the state of UK chemistry. I’m going to take two areas that I know a bit about, chemoinformatics and polymers (specifically polymer informatics as we were sponsored by Unilever for a 4-year project). Both of these are represented by Bourne as the lowest quality of chemistry (presumably in UK?). I am naturally upset at being repsented as working in areas of very low quality – I believe it is the scientist and the actual science performed that should be judged – not the discipline. (There are limits to this, such as homeopathy, and creationism, but all the sciences in Bourne are mainstream hypothesis- or data-driven science). Let’s remember that Einstein worked in a patent office and van’t Hoff in a vetinary school (for which he was lambasted by Wislicenus).

There is no mention of chemoinformatics in R2009. If Bourne took that as an indication of quality that’s completely unjustified. Here’s polymers (my emphasis):

P 17: There are examples of excellence

that can be readily identified in synthesis, catalysis

including biocatalysis, biological chemistry (specifically

bioanalytical), supramolecular chemistry, polymers and

colloids and gas-phase spectroscopy and dynamics.

P21: Polymer Science and Engineering

Following world-wide trends, the UK polymer chemistry

community has made some important and

excellent choices. In a coordinated action a few

universities have set-up excellent programmes

covering the entire chain-of-knowledge in polymer

science and engineering. In this way, the UK is

ensured a leading position in this important field for

both scientific and industrial needs. There is strong

evidence of growth and impact in polymer synthesis in

the UK Chemistry community. There are several

centres that have been created and whose members

have established international reputations. The

polymer synthesis community has placed the field on

the map in the UK. There is interest in controlled

polymer synthesis, water-processible and functional

polymers. A very strong activity that has international

recognition is the synthesis and processing of organic

electronic materials where the UK is pre-eminent.

Applications include polymer LEDs field effect

transistors, organic photovoltaics and sensors.

This bears no relation to the low quality for “Structural Polymers and technology”.

Bourne labels chemoinformatics as the lowest quality of all: “Refocus – funding targeted towards identified priorities”. A simple reading of this is “you (==me) have been doing rubbish work and we are going to reform you”. Like a failing school.

So if this is going to happen, at least I need to know the reason for it. Who made the decision, on what evidence. If the evidence is there (even that a group of the great-and-the-good made the plot), I’ll comment objectively. Scientists are used to being told their work is poor or misguided – it one of the strengths of science.

But so far the community as a whole seems to be finding it hard to get hard evidence.