I’ve had two comments / tweets recently that have expanded my horizons:

Todd Vision says: October 6, 2011 at 8:59 am

Todd Vision says: October 6, 2011 at 8:59 am

I’d be curious to hear from those who have used services like Deep Dyve (http://www.deepdyve.com/) whether their model somewhat address the affordability and accessibility issues raised here.

And Heather Morrison:

it’s important to understand where pay-per leads see also my book chapter re schol comm summit.sfu.ca/item/429

I’ll quote from Heather later. I hadn’t come across DeepDyve before – it’s been going 3+ years and initially appeared to be a deep-web indexer but now is a portal for a variety of publisher articles. In other words it is a single pay-per-view “solution” aggregating over a wide range of publishers (though it is not clear for how many they actually have full text rather than abstracts). Among the FAQ..

We are the largest online rental service, offering full-text access to millions of articles across thousands of journals from the world’s leading publishers, including Springer, Nature Publishing Group, Wiley-Blackwell and more. Our mission is to make authoritative information more affordable and accessible to users who are “unaffiliated” with a large institution and therefore lack easy and affordable access to these vital sources of information.

At least they are honest and use the word RENTAL.

you can “rent” an article which allows you to view-only the full article from the DeepDyve site for 24 hours (or more), but you cannot print or download the document. With DeepDyve, you get reduced access in exchange for a massively reduced price — up to 90% off the cost of purchasing the document.

Apparently they offer much reduced costs (remember the average for publisher-site PPV is ca 30 USD). In other places they say “0.99 USD”. Of course this may not be their average either. (they also offer “free access” to “open Access” papers).

Note that they do not allow saving, printing and I’d guess the product is ultra crippled (no copy-paste, no clicking) with added DRM (Digital Rights Management).

So what’s my take? First, of course the monopoly pricing of the publishers themselves is so horrific, so immoral and so unjustified that there is huge scope for price cutting. This simply emphasizes that we are effectively the victims of a cartel (why do all publishers charge the same and rent for 1 day? Who dreamt that up? Probably a rights collector “dear publisher, you can really fleece these customers – they have no union or cohesion – soak them for whatever you can). Oh, in case you had forgotten, scientists GIVE these people content.

So isn’t 99 cents a paper an equitable solution?

Possibly. I’m not saying that there isn’t a reasonable price for making publications available. But my concern is different. This is a market which looks either like a cartel or a monopoly. And those are intrinsically evil. It’s also something where the product is decide by sheer capitalism, not what is appropriate. *I* write a paper, the cartel decide to dumb it down to a level where my contribution is destroyed. There is no sense of serving the community (which after all provides the whole income) in creating a worthy information product.

I am also worried that this will destroy any role academia has in scientific publishing. We are getting to the stage where commercial companies are starting to run our business. Let’s take the model of Trinity (TX, US) http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=lib_faculty . This recent report shows the costs of traditional subscriptions against pay-per-view. I haven’t read it in detail but the conclusion is:

I approached this study as a strong proponent of pay-per-view journal article access, and my

research reinforces this position. Trinity has saved a significant amount on Elsevier articles

since 2007, far more than anticipated when we deposited what we thought would be our first

annual payment of $50,000 in a pay-per-view account. Moreover, pay-per-view has been a

popular service for those faculty members who have utilized it. We are now ready to increase

our usage and cost by making the process easier for our faculty and students.

Additional savings may result from establishing other pay-per-view arrangements, especially for

the Wiley-Blackwell journals. As a colleague at Colgate noted, “As with anything, there is risk

involved that they will change the model if enough users switch to token access, but compared

to canceling titles and having no access, it seems a reasonable risk” (Poulin). Our cancellation

of all Elsevier journals was certainly a risk, but the results have far outweighed the initial

concerns and the effort it took to start the program. To quote all kinds of people (including one

of my favorite brothers): Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

I assume that this is costed on something approaching 30 USD per view and not 1 USD. If, indeed, the negotiable costs of bulk provision can be sharply reduced then PPV becomes attractive to bean-counters.

The logical next step is to develop the PPV market direct to individuals and to cut out the library altogether. It frightens me, because the same approach could also be applied to textbooks. A monopoly publisher who offered solutions for students and researchers. There is obviously so much profit and slack in the system that the publisher complex has great freedom to undercut, lockin, etc.

My concern is academic and scientific freedom. The scientific author is treated like a commodity such as a crop or a mineral – something inanimate without rights. It debases scientific publishing and reduces the debates to numerology. Maybe I am living in a dream world and we are there already – the main role of academia is to provide a market for information monopolists and to deliver managed commodity education.

Heather’s concern is different and complementary – that we are reducing the free use of scholarship by pricing it per view. That we only do as much scholarship as we can afford to pay for, not as much as we want. And that we create a substandard result because we cannot pay to read as much as we should.

And that’s a small step towards academic NewSpeak (Orwell) where the publishers serve up material in a way that is convenient and profitable for them, not as the scholarship demands.

Here’s Heather…

The danger of usage-based pricing

The ready availability of quality, reliable usage-based data raises the possibility of pricing based on usage. At face value, usage-based pricing does seem fair. Those who use a resource heavily pay the most, smaller users pay less. Indeed, there is much to say for considering usage when developing pricing models. Usage data can come in handy, for example, to determine the relative value of a resource for different types or sizes of libraries, and price accordingly. One example, using an FTE-based pricing model, would involve comparing the relative usage of resources at two-year colleges as compared to that at four-year universities. A resource that is used somewhat less at two-year colleges in general could be weighted to 75% FTE for colleges, while a resource that is used a great deal less at two-year colleges could be weighted at 50% FTE for these colleges.

There is much to be said for offering usage-based pricing, or the “pay by the drink” model, on an optional basis, when some libraries are unable to afford needed subscriptions. For obvious reasons. this is much better than no access at all.

However, if a pricing model based on usage were to become prevalent, there are some real dangers, as there are disincentives to use with usage-based pricing.

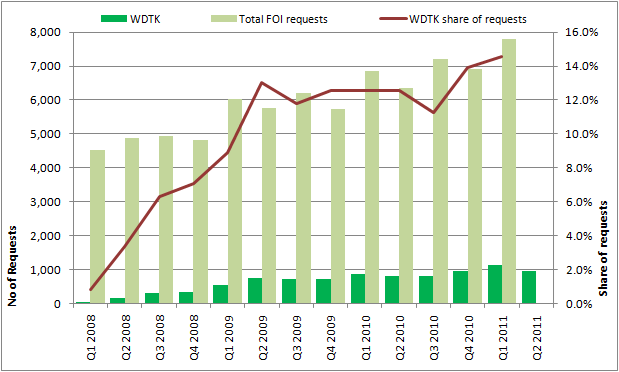

As Andrew Odlyzkow, Director, Digital Technology Centre, University of Minnesota, referring to internet usage pricing models, characterized it: “Usage-sensitive pricing is effective. The problem is that many of its effects are undesirable. In particular, such pricing lowers demand, often by substantial factors” (Odlyzkow 2001). For example, when AOL switched from usage-based to flat pricing for its users in 1996, usage tripled. This effect has been replicated in other countries and cultures. Research has shown that, with internet usage, even small charges discourage use, even if the charges are small enough that even heavy usage would be less than flat pricing.

While this research is based on Internet, rather than on print information resources and on individuals, rather than libraries, it makes sense that the same principles would apply to libraries and institutions as well. Picture, for example, a cash-strapped university looking for ways to cut the budget. With usage-based pricing, eliminating research papers at the first- or second-year level, eliminating the hands-on or exercise-based portion of an information literacy program, or scrapping an information literacy program altogether, would all be ways to achieve cost savings.

If the cost of use is known, there is a danger that a cash-strapped library will pass the cost along to the user, resulting in the direct disincentives to the user that Odlyzkow describes. This has been the tendency for many libraries with interlibrary loans, an area where libraries themselves have implemented usage-based fees deliberately, in order to limit demand (Budd 1989). Clinton (1999) discusses about how libraries in the United Kingdom have implemented user fees for interlibrary loans, to discourage what they see as indiscriminate use of the service.

With a print-based collection, users are free to browse to their heart’s content. As a researcher, the author has often browsed extensively, often in journals not obviously related to the research topic, looking for new approaches or research methods, or possibly knowledge from one discipline that might have implications in another. If libraries move to electronic-only collections and pay on the basis of usage, this kind of cross-disciplinary research might well be perceived as costly. Readers and researchers might be discouraged from browsing for the sake of curiosity, and be asked to limit their reading to what might be clearly justifiable economically. Learning and certain types of research, such as interdisciplinary research, would suffer.

To conclude, pricing based upon usage appears to not be optimal for scholarly research, due to the likelihood of it discouraging use.