In the current series of posts I argue that data should be Open and re-usable and that we should be allowed to use robots to extract it from publishers’ websites. A common counter argument is that data should be aggregated by secondary publishers who add human criticism to the data, improve it, and so should be allowed to resell it. We’ll look at that later. But we also often see a corollary expressed as the syllogism:

- all raw data sets contain some errors

- any errors in a data set render it worthless

- therefore all raw datasets are worthless and are only useful if cleaned by humans

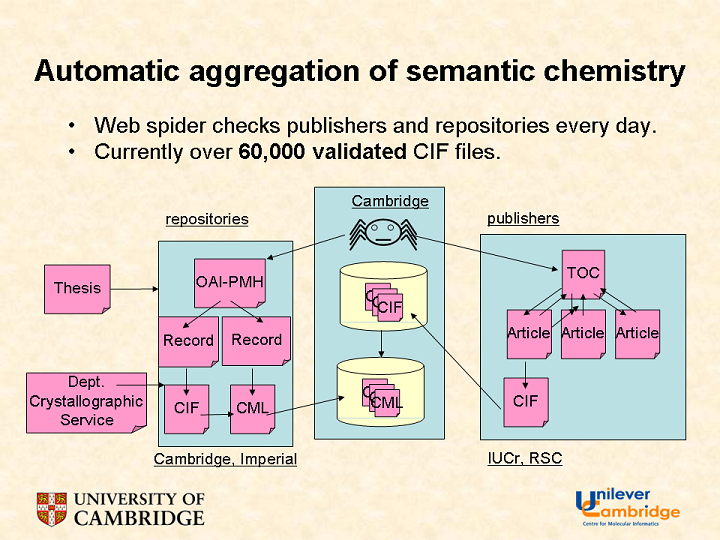

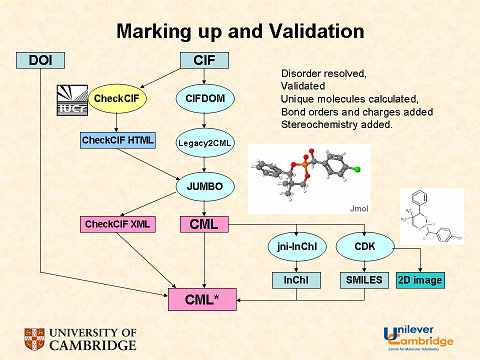

We would all agree that human data aggregation and cleaning is expensive and requires a coherent business model. However I have argued that the technology of data collection and the added metadata can now be very high and that “raw” data sets, such as CrystalEye can be of very high quality and, if we can assess the quality automatically, can make useful decisions as to what purposes it is fit for.

In bioscience it is well appreciated that no data is perfect, and that everything has to be assessed in the context of current understanding. There is no “sequence of the human genome” – there are frequent releases which reflect advances in technology, understanding and curation. The Ensembl genome system is on version 45. We are going to have to embrace the idea that whenever we use a data set we need to work out “how good it is”.

That is a major aspect of the work that our group does here. We collect data in three ways:

- text-mining

- data-extraction

- calculation and simulation

None of these is perfect but the more access to them and their metadata, the better off we are.

There are a number of ways of assessing the quality of a dataset.

- using two independent methods to determine a quantity. If they disagree then at least one of them has errors. If they agree within estimated error then we can hypothesize that the methods, which may be experimental or theoretical, are not in error. We try to disprove this hypothesis by devising better experiments or using new methods.

- relying on expert humans to pass judgement. This is good but expensive and, unfortunately, almost always requires cost-recovery that means the data are not re-usable. Thus the NIST Chemistry WebBook is free-to-read for individual compounds but the data set is not Open. (Note that while most US governments works are free of copyright there are special dispensations for NIST and similar agencies to allow cost-recovery).

- relying on the user community and blogosphere to pass judgement. This is, of course, a relatively new approach but also very powerful. If every time someone accesses a data item and reports an error the data set can be potentially enhanced. Note that this does not mean that the data are necessarily edited, but that a annotation is added to the set. This leads to communal curation of data – fairly common in bioscience – virtually unknown in chemistry since – until now – almost all data sets were commercially owned and few people will put effort into annotating something that they do not – in some sense – own. The annotation model will soon be made available on CrystalEye.

- validating the protocol that is used to create or assess the data set. This is particularly important for large sets where there is no way of predicting the quantities. There are 1 million new compounds published per year, each with ca 50 or more data points – i.e. 50 megadata. This is too much for humans to check so we have to validate the protocol that extracts the data from the literature.

The first three approaches are self-explanatory, but the fourth needs comment. How do we validate a protocol? In medicine and information retrieval (IR) it is common to create a “gold standard“. Here is WP on the medical usage:

In medicine, a gold standard test is a diagnostic test or benchmark that is regarded as definitive. This can refer to diagnosing a disease process, or the criteria by which scientific evidence is evaluated. For example, in resuscitation research, the gold standard test of a medication or procedure is whether or not it leads to an increase in the number of neurologically intact survivors that walk out of the hospital.[1] Other types of medical research might regard a significant decrease in 30 day mortality as the gold standard. The AMA Style Guide prefers the phrase Criterion Standard instead of Gold Standard, and many medical journals now mandate this usage in their instructions for contributors. For instance, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation specifies this usage.[1].

A hypothetical ideal gold standard test has a sensitivity of 100% (it identifies all individuals with a disease process; it does not have any false-negative results) and a specificity of 100% (it does not falsely identify someone with a condition that does not have the condition; it does not have any false-positive results). In practice, there are no ideal gold standard tests.

In IR the terms recall and precision are normally used. Again it is normally impossible to get 100% and so values of 80% are common. Let’s see a real example from OSCAR3 operating on an Open Access thesis from St Andrews University[1]. OSCAR3 is identifying (“retrieving”) the chemicals (CM) in the text and OSCAR’s results are underlined; at this stage we ignire whether OSCAR actually knows what the compounds are.

In 1923, J.B.S. datastore[‘chm180’] = { “Text”: “Haldane”, “Type”: “CM” } Haldane introduced the concept of renewable datastore[‘chm181’] = { “Element”: “H”, “Text”: “hydrogen”, “Type”: “CM” } hydrogen. datastore[‘chm182’] = { “Text”: “Haldane”, “Type”: “CM” } Haldane stated that if datastore[‘chm183’] = { “Element”: “H”, “Text”: “hydrogen”, “Type”: “CM” } hydrogen derived from wind power via electrolysis were liquefied and stored it would be the ideal datastore[‘chm184’] = { “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:33292”, “Text”: “fuel”, “Type”: “ONT” } fuel of the future. [5] The depletion of datastore[‘chm185’] = { “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:35230”, “Text”: “fossil fuel”, “Type”: “ONT” } fossil fuel resources and the need to reduce climate-affecting emissions (also known as green house gases) has driven the search for alternative energy sources. datastore[‘chm186’] = { “Element”: “H”, “Text”: “Hydrogen”, “Type”: “CM” } Hydrogen is a leading candidate as an alternative to datastore[‘chm187’] = { “Text”: “hydrocarbon”, “Type”: “CM” } hydrocarbon fossil fuels. datastore[‘chm188’] = { “Element”: “H”, “Text”: “Hydrogen”, “Type”: “CM” } Hydrogen can have the advantages of renewable production from datastore[‘chm189’] = { “Element”: “C”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:27594”, “Text”: “carbon”, “Type”: “CM” } carbon-free sources, which result in datastore[‘chm190’] = { “ontIDs”: “REX:0000303”, “Text”: “emission”, “Type”: “ONT” } emission levels far below existing datastore[‘chm191’] = { “ontIDs”: “REX:0000303”, “Text”: “emission”, “Type”: “ONT” } emission standards. datastore[‘chm192’] = { “Element”: “H”, “Text”: “Hydrogen”, “Type”: “CM” } Hydrogen can be derived from a diverse range of sources offering a variety of production methods best suited to a particular area or situation.[6] datastore[‘chm193’] = { “Element”: “H”, “Text”: “Hydrogen”, “Type”: “CM” } Hydrogen has long been used as a datastore[‘chm194’] = { “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:33292”, “Text”: “fuel”, “Type”: “ONT” } fuel. The gas supply in the early part of the 20th century consisted almost entirely of a coal gas comprised of more than 50% datastore[‘chm195’] = { “Element”: “H”, “Text”: “hydrogen”, “Type”: “CM” } hydrogen, along with datastore[‘chm196’] = { “cmlRef”: “cml5”, “SMILES”: “[H]C([H])([H])[H]”, “InChI”: “InChI=1/CH4/h1H4”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:16183”, “Text”: “methane”, “Type”: “CM” } methane, datastore[‘chm197’] = { “cmlRef”: “cml6”, “SMILES”: “[C-]#[O+]”, “InChI”: “InChI=1/CO/c1-2”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:17245”, “Text”: “carbon monoxide”, “Type”: “CM” } carbon monoxide, and datastore[‘chm198’] = { “cmlRef”: “cml7”, “SMILES”: “O=C=O”, “InChI”: “InChI=1/CO2/c2-1-3”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:16526”, “Text”: “carbon dioxide”, “Type”: “CM” } carbon dioxide, known as “town gas”.

Before we can evaluate how good this is we have to agree on what the “right” result is. Peter Corbett and Colin Batchelor spent much effort on devising a set of rules that tell us what should be regarded as a CM. Thus, for example, “coal gas” and “hydrocarbon” are not regarded as CMs in their guidelines but “hydrogen” is. In this passage OSCAR has found 12 phrases (mainly words) which it think are CM. Of these 11 are correct but one (“In”) is a false positive (OSCAR thinks this is the element Indium). OSCAR has not missed any, so we have:

True positives = 11

False positives = 1

False negatives = 0

So we have a recall of 100% (we got all the CMs) with a precision of 11/12 == 91%. It is, of course, easy to get 100% recall by marking everything as a CM so it is essential to report the precision as well. The average of these quantities (more strictly the harmonic mean) is often called the F or F1 score.

In this example OSCAR scored well because the compounds are all simple and common. But if we have unusual chemical names OSCAR may miss them. Here’s an example from another thesis [2]:

and datastore[‘chm918’] = { “cmlRef”: “cml42”, “SMILES”: “N[C@H](Cc1c[nH]c2ccccc12)C(O)=O”, “InChI”: “InChI=1/C11H12N2O2/c12-9(11(14)15)5-7-6-13-10-4-2-1-3-8(7)10/h1-4,6,9,13H,5,12H2,(H,14,15)/t9-/m1/s1/f/h14H”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:16296”, “Text”: “D-tryptophan”, “Type”: “CM” } D-tryptophan and some datastore[‘chm919’] = { “cmlRef”: “cml1”, “SMILES”: “NC(Cc1c[nH]c2ccccc12)C(O)=O”, “InChI”: “InChI=1/C11H12N2O2/c12-9(11(14)15)5-7-6-13-10-4-2-1-3-8(7)10/h1-4,6,9,13H,5,12H2,(H,14,15)/f/h14H”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:27897”, “Text”: “tryptophan”, “Type”: “CM” } tryptophan and datastore[‘chm920’] = { “cmlRef”: “cml2”, “SMILES”: “c1ccc2[nH]ccc2c1”, “InChI”: “InChI=1/C8H7N/c1-2-4-8-7(3-1)5-6-9-8/h1-6,9H”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:16881 CHEBI:35581”, “Text”: “indole”, “Type”: “CM” } indole derivatives (1) and datastore[‘chm921’] = { “cmlRef”: “cml42”, “SMILES”: “N[C@H](Cc1c[nH]c2ccccc12)C(O)=O”, “InChI”: “InChI=1/C11H12N2O2/c12-9(11(14)15)5-7-6-13-10-4-2-1-3-8(7)10/h1-4,6,9,13H,5,12H2,(H,14,15)/t9-/m1/s1/f/h14H”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:16296”, “Text”: “D-tryptophan”, “Type”: “CM” } D-tryptophan and datastore[‘chm922’] = { “cmlRef”: “cml42”, “SMILES”: “N[C@H](Cc1c[nH]c2ccccc12)C(O)=O”, “InChI”: “InChI=1/C11H12N2O2/c12-9(11(14)15)5-7-6-13-10-4-2-1-3-8(7)10/h1-4,6,9,13H,5,12H2,(H,14,15)/t9-/m1/s1/f/h14H”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:16296”, “Text”: “D-tryptophan”, “Type”: “CM” } D-tryptophan and datastore[‘chm923’] = { “cmlRef”: “cml42”, “SMILES”: “N[C@H](Cc1c[nH]c2ccccc12)C(O)=O”, “InChI”: “InChI=1/C11H12N2O2/c12-9(11(14)15)5-7-6-13-10-4-2-1-3-8(7)10/h1-4,6,9,13H,5,12H2,(H,14,15)/t9-/m1/s1/f/h14H”, “ontIDs”: “CHEBI:16296”, “Text”: “D-tryptophan”, “Type”: “CM” } D-tryptophan (1) (1) (1)

Halometabolite PrnA / datastore[‘chm925’] = { “Text”: “PrnC”, “Type”: “CM” } PrnC

datastore[‘chm927’] = { “Text”: “Pyrrolnitrin”, “Type”: “CM” } Pyrrolnitrin (5) datastore[‘chm928’] = { “Text”: “Rebeccamycin”, “Type”: “CM” } Rebeccamycin (6) datastore[‘chm929’] = { “Text”: “Pyrrindomycin”, “Type”: “CM” } Pyrrindomycin (7) datastore[‘chm930’] = { “Text”: “Thienodolin”, “Type”: “CM” } Thienodolin (8) datastore[‘chm931’] = { “Text”: “Pyrrolnitrin”, “Type”: “CM” } Pyrrolnitrin (9) datastore[‘chm932’] = { “Text”: “Pentachloropseudilin”, “Type”: “CM” } Pentachloropseudilin (10) Pyoluteorin (11) –

Here OSCAR has missed “Pyoluteorin” (see Pubchem for the structure) and we have 12 true positives and 1 false negative. So we have recall of 12/13 == 91% and precision of 100%.

Peter Corbett measures OSCAR3 ceaselessly. It’s only as good as the metrics. Read his blog to find out where he’s got to. But I had to search quite hard to find false negatives. It’s also dependent on the corpus used – the two examples are quite different sorts of chemistry and score differently.

Unfortunately this type of careful study is uncommon in chemistry. Much of the software and information is commercial and closed. So you will hear vendors tell you how good their text-mining software or descriptors or machine-learning are. And there are hundreds of papers in the literature claiming wonderful results. Try asking them what their gold standard is; what is the balance between precision and recall. If they look perplexed or shifty don’t buy it.

So why is this important for cyberscience? Because we are going to use very large amounts of data and we need to know how good it is. That can normally only be done by using robots. In some cases these robots need a protocol that has been thoroughly tested on a small set – the gold standard – and then we can infer something about the quality of the data of the rest. Alternatively we develop tools for analysing the spread of the data, consistency with know values, etc. It’s hard work, but a necessary approach for cyberscience. And we shall find, if the publishers let us have access to the data, that everyone benefits from the added critical analysis that the robots bring.

[1] I can’t find this by searching Google – so repository managers make sure your theses are well indexed by search engines. Anyway, Kelcey, many thanks for making your thesis Open Access.

[2] “PyrH and PrnB Crystal Structures”, School of Chemistry and Centre for Biomolecular Sciences University of St Andrews, Walter De Laurentis, December 2006, Supervisor Prof. J datastore[‘chm8’] = { “Element”: “H”, “Text”: “H”, “Type”: “CM” } H Naismith

I shall adopt the same naming method, making licenses explicit when talking about specific journals, publishers or whatever. I think this will go a long way towards alleviating confusion/term dilution, and also towards fixing in the consumers’ (researchers’) minds that OA must come with a licence in order to be useful.

I suggest one other way forward: pay careful attention to mandates as they are established. If they are worded clearly, much publisher weaseling can be pre-empted; if the publishing lobby and their pet pit-bulls get their way, the mandates we end up with will be full of loopholes.