Chemical research has traditionally been organized in either experiment-centric or molecule-centric models.

This makes sense from the chemist’s standpoint.

When we think about doing chemistry, we conceptualize experiments as the fundamental unit of progress. This is reflected in the laboratory notebook, where each page is an experiment, with an objective, a procedure, the results, their analysis and a final conclusion optimally directly answering the stated objective.

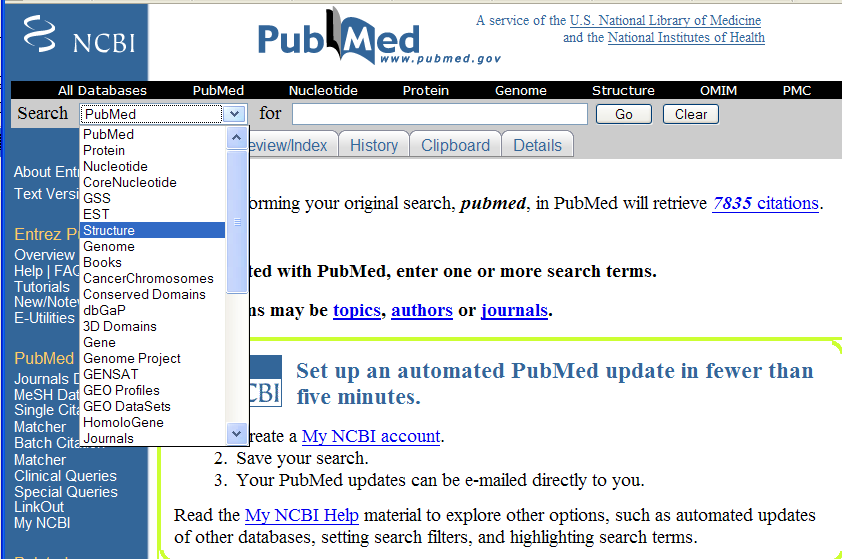

When we think about searching for chemistry, we generally imagine molecules and transformations. This is reflected in the search engines that are available to chemists, with most allowing at least the drawing or representation of a single molecule or class of molecules (via substructure searching).

But these are not the only perspectives possible.

What would chemistry look like from a results-centric view?

Lets see with a specific example. Take EXP150, where we are trying to synthesize a Ugi product as a potential anti-malarial agent and identify Ugi products that crystallize from their reaction mixture.

If we extract the information contained here based on individual results, something very interesting happens. By using some standard representation for actions we can come up with something that looks like it should be machine readable without much difficulty:

- ADD container (type=one dram screwcap vial)

- ADD methanol (InChIKey=OKKJLVBELUTLKV-UHFFFAOYAX, volume=1 ml)

- WAIT (time=15 min)

- ADD benzylamine (InChIKey=WGQKYBSKWIADBV-UHFFFAOYAL, volume=54.6 ul)

- VORTEX (time=15 s)

- WAIT (time=4 min)

- ADD phenanthrene-9-carboxaldehyde (InChIKey=QECIGCMPORCORE-UHFFFAOYAE, mass=103.1 mg)

- VORTEX (time=4 min)

- WAIT (time=22 min)

- ADD crotonic acid (InChIKey=LDHQCZJRKDOVOX-JSWHHWTPCJ, mass=43.0 mg)

- VORTEX (time=30 s)

- WAIT (time=14 min)

- ADD tert-butyl isocyanide (InChIKey=FAGLEPBREOXSAC-UHFFFAOYAL, volume=56.5 ul)

- VORTEX (time=5.5 min)

- TAKE PICTURE

It turns out that for this CombiUgi project very few commands are required to describe all possible actions:

- ADD

- WAIT

- VORTEX

- CENTRIFUGE

- DECANT

- TAKE PICTURE

- TAKE NMR

By focusing on each result independently, it no longer matters if the objective of the experiment was reached or if the experiment was aborted at a later point.

Also, if we recorded chemistry this way we could do searches that are currently not possible:

-

What happens (pictures, NMRs) when an amine and an aromatic aldehyde are mixed in an alcoholic solvent for more than 3 hours with at least 15 s vortexing after the addition of both reagents?

-

What happens (picture, NMRs) when an isonitrile, amine, aldehyde and carboxylic acid are mixed in that specific order, with at least 2 vortexing steps of any duration?

I am not sure if we can get to that level of query control, but ChemSpider will investigate representing our results in a database in this way to see how far we can get.

Note that we can’t represent everything using this approach. For example observations made in the experiment log don’t show up here, as well as anything unexpected. Therefore, at least as long as we have human beings recording experiments, we’re going to continue to use the wiki as the official lab notebook of my group. But hopefully I’ve shown how we can translate from freeform to structured format fairly easily.

Now one reason I think that this is a good time to generate results-centric databases is the inevitable rise of automation. It turns out that it is difficult for humans to record an experiment log accurately. (Take a look at the lab notebooks in a typical organic chemistry lab – can you really reproduce all those experiments without talking to the researcher?)

But machines are good at recording dates and times of actions and all the tedious details of executing a protocol. This is something that we would like to address in the automation component of our next proposal.

Does that mean that machines will replace chemists in the near future? Not any more than calculators have replaced mathematicians. I think that automating result production will leave more time for analysis, which is really the test of a true chemist (as opposed to a technician).

Here is an example

[…]

database, as long as attribution is provided. (If anyone knows of any accepted XML for experimental actions let me know and we’ll adopt that.)

I think this takes us a step closer from freeform Open Notebook Science to the chemical semantic web, something that both Cameron Neylon and I have been discussing for a while now.

PMR: This is very important to follow – and I’ll give some of our insights. Firstly, we have been tackling this for ca. 5 years, starting from the results as recorded in scientific papers or theses. Most recently we have been concentrating very hard on theses and have just taken delivery of a batch of about 20, all from the same lab.

I agree absolutely with J-C that traditional recording of chemical syntheses in papers and theses is very variable and almost always misses large amounts of essential details. I also agree absolutely that the way to get the info is to record the experiment as it happens. That’s what the Southampton projects CombeChem and R4L spent a lot of time doing. The rouble is it’s hard. Hard socially. Hard to get chemists interested (if it was easy we’d be doing it by now). We are doing exactly the same with some industrial partners. They want to keep the lab book.The paper lab book. That’s why electronic notebook systems have been so slow to take off. The lab book works – up to a point – and it also serves the critical issues of managing safety and intellectual property. Not very well, but well enough.

J-C asks

If anyone knows of any accepted XML for experimental actions let me know and we’ll adopt that

CML has been designed to support and Lezan Hawizy in our group has been working in detail over the last 4 months to see if CML works. It’s capable of managing inter alia:

- observations

- actions

- substances, molecules, amounts

- parameters

- properties (molecules and reactions)

- reactions (in detail) with their conditions

- scientific units

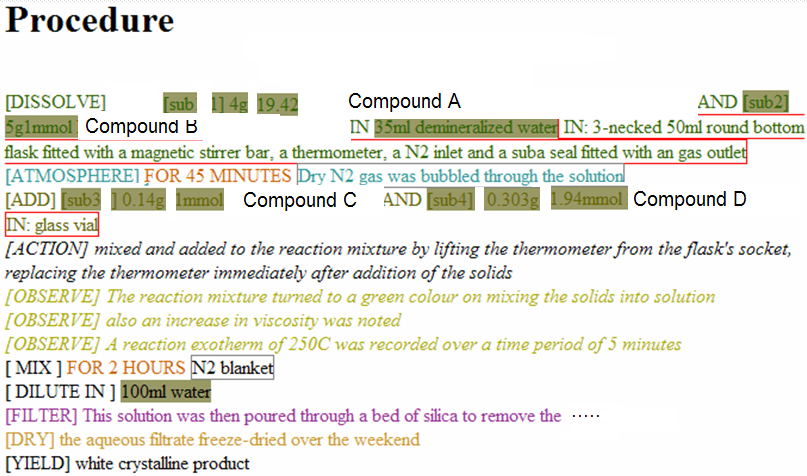

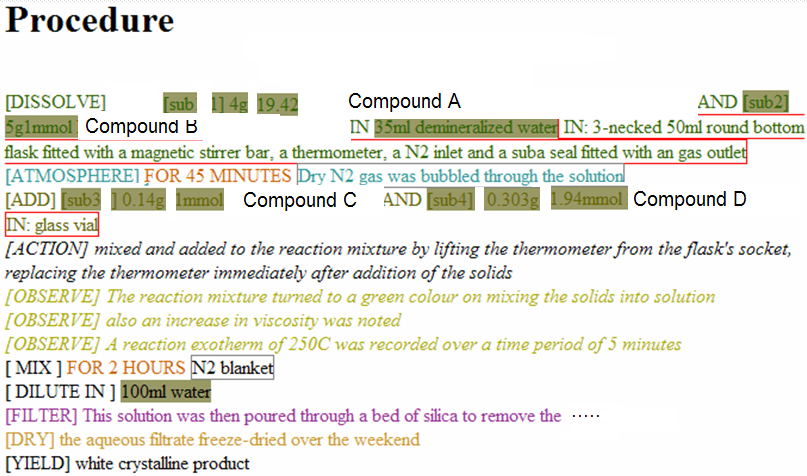

We have now taken a good subset of literature reactions (abbreviated though they may be) and worked out some of the syntactic, semantic, ontological and lexical environment that is required. Here is a typical result, which has a lot in common with J-C’s synthesis.

(Click to enlarge. ) I have cut out the actual compounds though in the real example they have full formulae in CML, and can be used to manage balance of reactions, masses, volumes, molar amounts, etc. JUMBO is capable of working out which reagents are present in excess, for example. It can also tell you how much of every you will need and how long the reaction will take. No magic, just housekeeping.

CML is designed with a fluid vocabulary, so that anything which isn’t already known is found in dictionaries and repositories. So we have collections of:

- solvents

- reagents

- apparatus

- procedures

- appearances

- units

- common molecules

A word of warning. It looks attractive, almost trivial, when you start. But as you look at more examples and particularly widen your scope it gets less and less productive. I’ve probably looked through several hundred papers. There is always a balance between precision and recall and Zipf’s law. You will never manage everything. There will be procedures, substances, etc, that defy representation. There are anonymous compounds and anaphora.

So we can’t yet build a semantic robot that is capable of doing everything. We probably can build examples that work in specific labs where the reactions are systematically similar – as in combinatorial chemistry.

So, yes, J-C – we would love to explore how CML can support this…