I have been trying to find “Open Access” articles published in Royal Society of Chemistry journals. It’s very difficult – Google doesn’t help – and I’ve scanned about 200 abstracts without finding one. Then I happened on http://blogs.rsc.org/cc/2012/10/08/chemcomm-celebrates-its-first-gold-for-gold-communication/ (I’ll reproduce it in full without permission but I have removed an image of a gold medal):

ChemComm celebrates its first Gold for Gold communication

08 Oct 2012

By Joanne Thomson.

A groundbreaking £1 million initiative to support British researchers

Eugen Stulz (University of Southampton) and colleagues are the first ChemComm

authors to publish a communication as part of our Gold for Gold initiative.

Their communication, entitled ‘A DNA based five-state switch with programmed reversibility’

is now free to access for all.

‘I’m delighted that Eugen’s communication is the first open access communication to be published in ChemComm using the RSC’s Gold for Gold programme,’ says Phil Gale, Head of Chemistry at the University of Southampton. ‘This open access programme will allow us to showcase our research to a much wider audience.’

Gold for Gold

is an innovative initiative rewarding UK RSC Gold customers with credits to publish a select number of papers in RSC journals via Open Science, the RSC’s Gold Open Access option.

Gold for Gold” is an RSC scheme where they will match funding for UK authors http://www.rsc.org/AboutUs/News/PressReleases/2012/gold-for-gold-rsc-open-access.asp . Excerpts include:

UK institutes who are RSC Gold customers will shortly receive credit equal to the subscription paid, enabling their researchers, who are being asked to publish Open Access but often do not yet have funding to pay for it directly, to make their paper available via Open Science, the RSC’s Gold OA option.

The Research Councils UK (RCUK) also published their revised policy on Open Access, requiring researchers to publish in OA compliant journals.

‘Gold for Gold’ seeks to support researchers until the block grants from RCUK are distributed next April, which, once established are intended to fund Gold OA. [PMR emphasis]

And Univ of Cambridge and JISC seem to think it a good idea:

Lesley Gray, Journals Co-ordinator Scheme Manager from the University of Cambridge, said: “This initiative by the RSC is welcomed, and will serve to promote Open Access publishing to researchers.”

Lorraine Estelle, Chief Executive of JISC congratulated the RSC on launching ‘Gold for Gold’ which “demonstrates the Society’s engagement with the chemical science community and recent Open Access developments”.

So what is Eugen Stulz and readers (and perhaps RCUK) getting for their money? Here’s the cover page of the article

What rights do readers have? Is this compliant with the RCUK definition of Gold which requires CC-BY at least? The phrase “RSC Open Science free article” is not-clickable (unlike “Open Access” buttons in BMC and PLoS. I cannot find any more information by Googling. So let’s look at the article – it should have some indication of authorship and copyright.

“This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012″

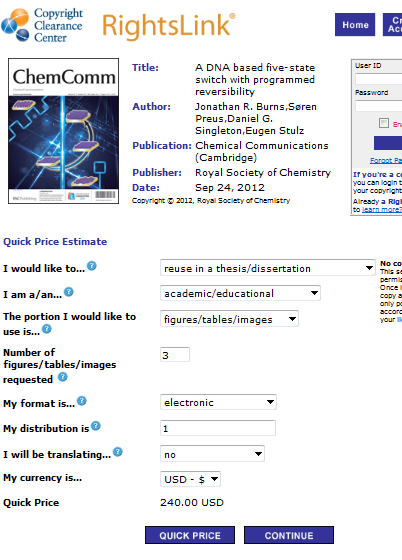

This is a very strange phrase which I have found consistently in RSC material. I don’t know what it means. There is no indication in the article that it is Open Access. I assume that almost anyone would assume this was an article in which the RSC claimed complete rights. So let’s go to “Request Permissions”. I’ll simulate a student asking for permission to re-use the three diagrams in her thesis> That’s a reasonable scientific thing to do. Indeed it could be scientifically irresponsible NOT to show other scientists’ data.

So here’s my request for a student to re-use the diagrams:

So even a student has to pay 240 USD for re-use of scientific data from this “Gold Open Access” article.

This is completely at odds with the RCUK policy of CC-BY for paid Open Access. RCUK read my blog and I hope they will make it quite clear to RSC that this is not in the letter or the spirit of paid Open Access.

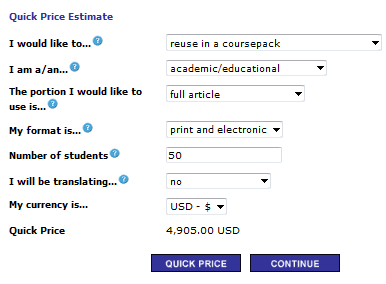

And if as a lecturer I wanted to give every student in a class of 50 a copy of this 3-page “Open Access” article:

[No rant]

It is simply incomprehensible that the RSC is unable to simply, properly propagate rights that people pay them for to do. It sounds to me a very basic part of “publishing” to me… If you can manage to put in dc:title information in the HTML, how can you forget to add the legal bits (dc:copyright, dc:license, or friends)?? More importantly, why does that fail at all? It’s neither technical, nor legal. It must be something in the structure by which responsibilities are scattered around in the organisation?

No doubt they will tell us.

We have found their re-use and permissions for paid-OA are generally not easy to understand.

Egon, as we look at our licensing, there is currently a gap on what we say on re-use rights for people who are neither authors (covered by a license to publish) or subscribers (covered by the contractual T&Cs). Will be covered shortly. Nothing more than that.

Richard, from my perspective, I am not worried about the actual license (though, of course, I have a preference :), but we all must work hard to be at least clear in what the license is. That is what is really important. Yet, this so often goes wrong. I am really wondering what causes that.

I wish I could say I am shocked. It seems the Royal Society of Chemistry is bent on proving that it does not represent the interests of chemistry, chemists, or wider society. A classic example of the tail wagging the dog.

Mike, I think that’s a rather sweeping statement to make from the evidence presented.

Come on, Richard. You know perfectly well that this fits a pattern of behaviour.

Erm – no, Mike.

Hi Peter

Thanks for the comments, I think there are three things you’re asking:

“This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012″ means pretty much what it says – as you know, we don’t ask authors to transfer their copyright to us, rather we’re granted a license to publish. So the copyright line refers to the journal and its expression, not the copyright of the academic work. You’ve seen it on the Supplementary Data as well.

On the specific license, you also realise the RCUK mandate is not yet in place – we’re looking at how we move to be compliant, but we have authors and co-owning societies to involve in the discussions. As I’ve said before, the current Open Science license doesn’t seem to have been a barrier to authors who wish to take this option.

The point on the charge for rights – yep, you’ve spotted a bug. It’s a mistake (i.e a default we need to fix) and from brief discussions today doubt very much we’ve taken any rights reuse income from the Open Science articles – but if anyone thinks they have, or we receive any between now and the fix, we’ll refund our charges. Thanks for letting us know.

Best wishes

Richard

So, how can we learn from these mistakes? It seems we are all making them again and again. Richard, what can we do to ensure license/copyright information propagation is on everyone’s mind set, so that people double check that that information is really propagated before the hit submit or send our that press release?

Very true, Egon. It’s good know this was a mistake (thanks, Richard) but it’s not isolated — I reported exactly the same thing for an Elsevier journal back in March: http://svpow.com/2012/03/21/pay-to-download-elseviers-open-access-articles/

The well-documented problems with Springer Images charging for the use of CC BY images falls into the same category.

I think it’s pretty clear what’s behind these pervasive mistakes: a long-establish culture of entitlement among publishers, and assumptions set to a default of “we own this”. What’s encouraging is the sense that most publishers, most of the time, are fixing these bugs when brought to their attention, which puts them on the right side of Hanlon’s Razor. The moral is that it’s up to us to scream blue murder whenever we see this kind of mistake. Credit to Peter for doing just that in this case.

Thanks, RIchard, this is helpful. Regarding copyright, I suggest that you clarify by stating (as some other journals) do: “article copyright the authors; collection copyright RSC”. As we move towards a world where people are much more aware of credit, attribution, copyright ownership, licences, etc., I hope we’ll see all publishers move towards being more explicit about their terms — even the ones whose terms I find unacceptable.

I would like to ask this forum what happens when a Gold article is “dis-assembled”. Thus I gather that the RSC and other publishers are working hard to produce an API, or application programmer interface. This means that software could make well defined calls into the journal collection of a publisher. It is perfectly possible that open source codes eg using such an API may become available. In effect, it is data mining by a different name. What rights would one have with respect to accessing the material originally contained in eg a Gold article as opposed to non-Gold content? Once dis-assembled and accessed via an API, is any of the original intent and meaning of a Gold article retained in any way? Would the data in a Gold article be treated differently?

Thus the RSC claims copyright for the Journal, but not necessarily for individual articles. But for content accessed via a Journal API, do we have to start from the beginning in terms of understanding our rights and how we can “use” what we used to call a journal article?

Hi Henry

Good question. In Open PHACTS we think we’ve a framework to integrate data but pass through the licensing of differently licensed data sets intact. But we’re also having to deal with the question of whether the transformed data source (to RDF) carries the same license as the original data, or whether it can be used to transition data sources to a standard interoperable license set. In these cases at least all the data within a particular collection is licensed the same way.

But with (say) an API into the RSC’s collection there’d be a mix of licenses – as the original licensed object is the article, I’m assuming any child/section of the article should be licensed as for the article and ideally license/reuse info would have to be attached to each snippet in the returned data.

Pingback: Unilever Centre for Molecular Informatics, Cambridge - Is the Royal Society of Chemistry really cheaper than ACS? RSC charge 50 USD PER STUDENT PER PAGE for teaching materials « petermr's blog

No surprise. A few months ago Elsevier was advertising their Open Archives like if it where full genuine OA. I was curious what they mean exactly by “Open” but wasn’t able to find any legal statement, so I asked their director of PR via Twitter:

https://twitter.com/wojnarski/status/200974225320841216

The reply was:

“we are in a test and learn phase, and experimenting with an array of OA licensing options. ”

https://twitter.com/wojnarski/status/202370407607697408

– how sweet, isn’t it? 🙂

Biggest publisher of academic literature has no idea on what terms they distribute 74 journals??? They’re in a “test and learn” phase and “experimenting” with an “array” of options… After 10-20 years of existence of Open Access movement, Elsevier is still “experimenting”! Wow!

I’m afraid that academic publishers think we are all plain idiots. Sorry, I can’t find any other explanation. I suspect Royal Society of Chemistry is a similar case – it’s not a family business run by a hobbyist in Nigeria who hasn’t heard about copyrights, is it? Richard Kidd’s explanations above go exactly along the same lines as Elsevier’s: “not yet in place”, “we’re looking at”, need more “discussions”, “it’s a mistake”.

If the policy is “not yet in place”, why do £2500 fees ARE already in place? If the publisher makes serious mistakes in doing their job, why don’t they do mistakes when charging fees? why don’t they let authors “mistakenly” publish in OA for free? There is a strange asymmetry in where the mistakes happen: always on publishers’ responsibility side and never on their income side (or maybe you’ve heard of an author who *mistakenly* was published for free?)

Really valuable reply, I will use parts of it in my next post on this area.

>>No surprise. A few months ago Elsevier was advertising their Open Archives like if it where full genuine OA. I was curious what they mean exactly by “Open” but wasn’t able to find any legal statement, so I asked their director of PR via Twitter:

https://twitter.com/wojnarski/status/200974225320841216

>>The reply was:

“we are in a test and learn phase, and experimenting with an array of OA licensing options. ”

https://twitter.com/wojnarski/status/202370407607697408

Well dome for getting a reply!

>>Biggest publisher of academic literature has no idea on what terms they distribute 74 journals??? They’re in a “test and learn” phase and “experimenting” with an “array” of options… After 10-20 years of existence of Open Access movement, Elsevier is still “experimenting”! Wow!

I have asked their “Director of Universal Access” for a list of all author-paid articles (so I could examine the licences) and she could only tell me that they had published about 1000 per year. It is plain irresponsibility to take 6 million dollars off authors and then not know where you have put the results.

>>I’m afraid that academic publishers think we are all plain idiots. Sorry, I can’t find any other explanation. I suspect Royal Society of Chemistry is a similar case – it’s not a family business run by a hobbyist in Nigeria who hasn’t heard about copyrights, is it? Richard Kidd’s explanations above go exactly along the same lines as Elsevier’s: “not yet in place”, “we’re looking at”, need more “discussions”, “it’s a mistake”.

They don’t think we are idiots. They think we don’t care. I and you and Ross Mounce and a few others DO care. The publishers regard us as unpleasant nuisances. They stall. They use weasel-words (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weasel_word ) designed to fudge, cover up inaction, mislead, stall, etc. They are in a perpetual state of “working this out” as you have found.

>>If the policy is “not yet in place”, why do £2500 fees ARE already in place? If the publisher makes serious mistakes in doing their job, why don’t they do mistakes when charging fees? why don’t they let authors “mistakenly” publish in OA for free? There is a strange asymmetry in where the mistakes happen: always on publishers’ responsibility side and never on their income side (or maybe you’ve heard of an author who *mistakenly* was published for free?)

Exactly my impression, and Mike Taylor’s. (see last post). At best it is Institutionalism. At worst it’s cynical greed.

There is no excuse for a large learned society not to understand pricing and use clear licences.

>>Really valuable reply, I will use parts of it in my next post on this area.

You’re welcome! Feel free to use whatever you need. I don’t have my own blog so if any part of any of my comments is worth re-posting just go on – CC-BY 🙂

>>I and you and Ross Mounce and a few others DO care. The publishers regard us as unpleasant nuisances.

Good! We can be proud! 🙂 When fighting in a good cause, it’s the right and unavoidable thing to become a nuisance for several people out there; there’s no other way to change things for the better.

>>They don’t think we are idiots. They think we don’t care.

Yep. Many people care, but we lack institutional support. What we need is an Authors’ and Readers’ advocacy group which would monitor what agreements are signed between publishers and authors, and take legal actions whenever the agreements are (1) unlawful, or (2) improperly executed by the publisher. Something like Free Software Foundation in open source world, who actively defends openness by sueing companies which breach open-source licenses. These days, scholars are customers who buy publishers’ services and like every customer they should be protected by “consumer law”. Maybe it’s time to start making use of the rights that we have? (I’m not a lawyer, but I’m sure we do have *some* rights?)

This advocacy organization could sue publishers on behalf of aggrieved authors and request financial compensations in cases like RSC. Everyone knows that mistakes happen, but it’s widely accepted in all civilized world that if a company or organization makes a mistake, it pays for it, in cash – saying “sorry” is far from enough. For most companies, the threat of a lawsuit is the only effective argument to force them into proper behavior. Currently, no matter what publishers do, there is no one who could sue them: any individual author is unable to do this, even if he cares. In this sense – because of the lack of intitutional support and legal power – we are treated like idiots: publishers can do what they want and we are forceless. If someone starts protesting, publishers “sell” us a nice piece of propaganda and deem the problem solved.

The organization which is probably best positioned to become such an advocate, is OKFN, for several reasons: (1) they’ve got established reputation as non-profit activists of openness; (2) have deep knowledge of copyright law; and (3) they’re private organization which – I believe – really understands the problem and cares about it, in contrast to most public institutions.

What’s very important, this kind of advocacy can be self-financing (or “sustainable” – publishers love this term!): the advocate can take a share in compensations awarded by the court, so there is no need to struggle hard to make a living, or to take funds from other projects to support this one.

At a low level, the actions could look something like this: pick randomly 10 papers from a given journal; send emails to authors asking for copies of agreements; check the agreements against unlawful clauses; check publisher’s website and see if the papers are properly published and accessible; if anything is wrong, ask authors for permission to sue on their behalf.

By the way, when contacting the authors, this organization could educate them on what rights they have and make them aware of consequences of agreements they sign (e.g., that if the license is not CC but a publisher’s custom stuff, its “openness” and future accessibility can be much lower than authors think) – this would influence authors’ future decisions and create pressure on publishers to take dialogue with academia seriously.

—

OK, that’s just a rough idea, I don’t know if feasible, but maybe a good starting point for a discussion?

Just to be VERY clear Marcin – when you refer to “in cases like RSC” above, none of your examples apply to RSC. Unlawful agreements, improperly executed agreements – NONE of this applies to RSC generally or specifically in this example.

Accuracy and evidence are important.

To reiterate – as the title of this blog post is still misleading – RSC does not and has not charged students for reuse of our “Gold OA” articles.

Whether any of these allegations applies to RSC or not, can only be judged by a court. What I claim is that VERY LIKELY at least one of these applies to RSC – for explanation see my reply to your other comment, below.

Also, I claim that from legal perspective, at least one of these SHOULD apply to RSC, because your practices are unfair towards authors and readers, and academia should be legally protected against such practices by consumer law (if it isn’t yet, the law should be adapted accordingly).

No, I’m not talking about charging students for reuse. Please re-read Peter’s original post once more. Both Peter and myself, and other commenters here, we are talking about much broader problem of licensing, of which students’ reuse is just a special case, used for illustration.

Marcin – this isn’t an issue about copyright. The policy not in place is reuse t&cs for non-subscribing readers.

On the minor assertion that default is always to be in favour of the publisher’s income, I can think immediately of decent chunks of the RSC Archive which are free to access as they didn’t fit an article model. Or that we run ChemSpider, for instance.

If you think all publishers (or even all subscription publishers) are the same, you will make serious errors of judgement.

Couple more things while I’m here on this “why are there only mistakes in the publishers’ favour” meme…

The simplest answer is that no-one looks for evidence for those examples. Cherry picking of evidence doesn’t just happen in the publication of drug trials.

Secondly – I’m not sure what to call it, not ironic exactly – but these comments come under the example of the first article published ‘Gold for Gold’, which results in free OA up to the value of the Gold subscription paid. We’re giving away free OA, to help institutions and authors navigate the changing funding agency mandates. It’s disappointing that this is completely unrecognised here. Perfection is hard for us all to attain.

*yes, I know, under our own license, and with an incorrect rights link

Oh, how sad, poor Royal Society of Chemistry. They charge as low as £2500 per paper, just to make ends meet, and so they expect at least basic understanding and recognition from the community for their immense pro-publico-bono efforts. Sorry for disappointing you 🙁

But maybe not yet everything is lost. If there is in fact “cherry picking” of evidence against publishers, you must have tons of examples where your mistakes worked in favor of the authors, don’t you? Can you share a few of them with us? Not too many, say, 3 would be enough for the beginning. I promise to express sympathy!

By the way. I realize that RSC is absolutely short of money, like all publishers, but don’t you view it as a right thing to do: compensating authors of the papers which were negatively impacted by YOUR mistakes in reuse policy? Maybe some readers wanted to reuse a given paper but they hit a paywall and went away without even filing a request? In this way, dissemination of the paper was impacted: the authors lost potential readers and new CITATIONS! You know that audience and citations are key in academic tenure, so losing them creates serious damage for authors. How do you want to compensate this damage? Will you, for instance, give back the fees paid for publications? I think this would be the right and fair thing to do in such a case, if only the publisher has respect for its authors (you surely have!).

>>Marcin – this isn’t an issue about copyright. The policy not in place is reuse t&cs for non-subscribing readers.

Richard, you are wrong: this is exactly an issue about copyright, reuse policy is a secondary matter. But I’m not sure if you – as an Informatics Manager – are the right person to discuss this issue on RSC’s behalf? Who in RSC is responsible for your copyright policies? Not an Informatics Manager, I guess?

Anyway, the main problem is about your promises and their fulfilment in regard to copyrights; what you advertise to authors and what you actually deliver for the £2500 fee. You advertise (intensely) one thing – “Open Access” – but deliver something very different – “free access” merely: no copying, no reuse, no redistribution, no derivatives, …

It’s like selling newest Jaguar F-Type model with the engine substituted by Mini Cooper’s one, and not informing the buyers about the change. You think this is lawful? I don’t. If you were a car dealer employing this kind of practices, you would get sued on the very next day after selling the 1st car – I’m certain that academia should adopt similar standards for dealing with unfair publishers.

>>If you think all publishers (or even all subscription publishers) are the same, you will make serious errors of judgement.

Richard, you’re absolutely right, I would never think so. Publishers and their business practices vary significantly. Take, for example, Springer. When Springer claims that they publish (selected articles) as Open Access, they do publish as Open Access: every paper is distributed on BOAI-compliant CC-BY licence and this fact is clearly indicated in a copyright statement in each paper. This is very different from RSC practices, isn’t it?

I raised exactly these questions FIVE years ago with the RSC and others:

/pmr/2007/07/12/open-access-elsevier-wiley-rsc/

Peter Suber wrote:

>>>These [PMR’s] are valuable studies, especially when supplemented by clarifying publisher responses (like Jan Velterop’s response to Peter’s post on Springer). When a hybrid program doesn’t claim to offer “open access”, then I don’t criticize it for falling short of the BBB definition of OA, even if I criticize it on other grounds. But some of the hybrid programs do claim to offer OA; and even when they carefully pick new terms and avoid promising OA, their access barriers should be well-documented to help authors, funders, and universities decide whether their fees are worth paying. Journals should clearly describe their access policies –OA or not– and when they don’t, we count on independent investigations like Peter[MR]’s.

PMR>>Until the RSC has a clear, simple licence, and until they have a transparent accounting practice showing that they are putting real money into this (rather than simply switching a view/noview button and assuming subscriptions remain unaltered) then Gold-for-Gold has no objective meaning.

Excellent! So they’ve been deceiving authors for over 5 years already?! Isn’t it about time to push for real changes?

As a first step, scholars themselves must realize and accept two basic facts.

Fact #1: publishers are businesses not charities.

In most cases, what publishers do they do for money, not for any greater good, no matter what they claim or what they call themselves (“royal society” or whatever). Therefore, they must be treated as businesses, which means: making them fully accountable for their acts, decisions and mistakes, whether accidental or intentional. The only way to make publishers accountable is by imposing and enforcing law that would regulate the market of academic publishing. — That’s NOT difficult!! — It’s natural that every industry and every market has some specific laws that protect consumers against unfair practices. For example, when a bank advertises new deposits with interest rates of 10%, they can’t subsequently request clients to sign 20-page agreements with 19th page saying in small font that interest rate is 5%! Or when a travel agency advertises trips to Canaries with accomodation in 5-star hotel, they can’t subsequently lodge their clients in Bed & Breakfast. If anything like this happens, it’s obvious that the service provider will be forced to pay damages on the basis of consumer law. Exactly the same should apply to Open Access: advertising non-OA services as if they were genuine OA is unfair and should be punished by consumer law. Especially that academic publishing market is NOT a free market: it’s an OLIGOPOLY, and for this reason consumers – authors and readers – require legal protection even more.

Fact #2: scholars are not beggars. They have rights.

They deliver high quality content; they pay huge money for publishers’ services (in subscriptions and APCs); and consequently: they have RIGHT to be treated fairly and to expect top professionalism – without mistakes – in how the services are performed. If publishers fail to deliver on their promises, scholars do NOT need to ask politely for corrections – they have full moral rights to sue publishers and request compensations in court, either individually or with support of an advocacy institution that would guard authors’ and readers’ rights.

I realize that scholars are not lawyers and putting theory into practice is not that easy, but I’m sure it’s doable. Even more: I’m confident that it’s the best time NOW to do this. If these ideas sound reasonably to you, Peter, and you think it’s worth to discuss them in more detail, we may continue this talk via email.

An update, to show we deliver on our commitments:

We’ve fixed the Rights Permissions problem on OA articles. Now also clear licence information on the article, including CC-BY as an option.

e.g. http://doi.org/mt4

And a couple of quotes on the RSC’s approach from the recent parliamentary hearings:

“There are some quite ingenious attempts to avoid [double-dipping], of which the Royal Society of Chemistry Gold for Gold scheme is one that we particularly welcome.”

Rt Hon David Willetts MP, Minister for Universities and Science

“The more that this type of thinking can be seen to permeate throughout the publishing industry, the better.”

Ron Egginton, Head, BBSRC and ESRC Team, Research Funding Unit, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills