Yesterday I abandoned my coding to write about scientific publishing:

/pmr/2011/07/09/what-is-wrong-with-scientific-publishing-and-can-we-put-it-right-before-it-is-too-late/

and I now have to continue in a hopefully logical, somewhat exploratory vein. I don’t have all the answers – I don’t even have all the questions – and writing these posts is taking me to new areas where I shall put forward half-formed ideas and await feedback (“peer-review”) from the community. The act of trying to express my ideas formally, for a critical audience, is helping to refine them. And I am hoping that where I am struggling for facts or prior scholarship that you will help. That’s not an excuse for laziness , it’s a realization that one person cannot address this problem by themselves.

This blog post *is* a scholarly publication. It addresses all the points that I feel are important – priority (not that this is critical), peer review, communication, re-use (if you want to), and archival (not perhaps formal, but this blog is sufficiently prominent that it gets cached. This may horrify librarians, but it’s good enough for me).

The only thing it doesn’t have is an ISI impact factor, and I’ll return to that. It does have measures of impact (Technorati, Feedburner, etc.) which measure readership and crawlership. (These are inaccurate – they recently dropped by a factor of 5 when the blog was renamed – I’d be interested to hear from anyone who cannot receive this blog for technical reasons (timeout, etc.)). Feedburner suggests that a few hundred people “read” this blog. There’s also Friendfeed (http://friendfeed.com/petermr ) where people (mainly well-aligned) comment and “like” posts; and Twitter where I have 650 followers (Glyn Moody has 10 times that) – a tweet linking to yesterday’s post has just appeared.

So the blog post fulfils the role of communication – two way communication – and has mechanisms for detecting and measuring this. As I write this I imagine the community for whom I am preparing these ideas and from whom I am hoping for feedback. Ambitiously I am hoping that this could become a communal activity – where there are several authors. (We do this all the time in the OKF – Etherpads, Wikis, etc.) And who knows, this document might end up as part of a Panton Paper. As you can tell I am somewhat enjoying this, though writing is often painful in itself.

I am going to describe new ideas (at least for me) about scholarly publishing. I am going to use “scholarly” as inclusive of “STM” and extending to other fields – because in many cases the translation is direct; where there are differences I will explicitly use STM. I like the word “scholarly” because it highlights the importance of the author (which is one of the current symptoms of the malaise – the commoditization of authorship). It also maps onto our ideas of ScholarlyHTML as one of the examples of how publication should be done.

Before my analysis I’ll give an example of the symptoms of the dystopia. This has reinforced me in my determination never to publish my ideas in a traditional “paper” for a conventional journal. Details are slightly hazy. I was invited – I think in 2007 – to write an article as part of an Issue on the progress of Open Access. Here it is

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S009879130800004X

Serials Review

Volume 34, Issue 1, March 2008, Pages 52-64

Open Data in Science

Peter Murray-Rusta,

aMurray-Rust is Reader in Molecular Informatics, Unilever Centre for Molecular Sciences Informatics, Department of Chemistry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1EW, UK

It will cost you 40 USD to rent it for ONE DAY. You are allowed to print it for personal use during this period.

*I* cannot read my own article and I do not have a copy.

The whole submission process was Gormenghastian and I have ended up being embittered by it. I asked for the article to be Open Access (Green) and believed that it would be available indefinitely so that I would not have to take a “PDF copy” (which is why I don’t have one). When I discovered that I could not read my own article I contacted the publishers and was told that I had agreed to it being Open for a year after which it would be closed. Maybe – I don’t remember this but there were 100+ emails and it may have slipped my unconscious mind. If I had been conscious of it, I would never have acquiesced. It’s a bizarre condition – let people read something and then cut them off for ever. It has no place in “scholarly communication” – more in the burning of the libraries.

I took the invitation as an exciting opportunity to develop new ideas and to get feedback, so I wrote to the author (whom I only know throw email) and explained my ideas. (If I appear critical of her anywhere it is because I am critical of the whole system). I explained that “Open data” was an exciting topic where text was inadequate and to show this I would create an interactive paper (a datument) with intelligent objects. It would give readers an opportunity to see the potential and challenges of data. This was agreed and I would deliver my manuscript as HTML. I also started the conversation on Openness of the resulting article. The only positive thing was that I established that I could post my pre-submission manuscript independently of Elsevier. (I cannot do this with publishers such as the American Chemical Society – they would immediate refuse the article). I decided to deposit it in “Nature Precedings” – an imaginative gratis service from NPG. http://precedings.nature.com/documents/1526/version/1 . This manuscript still exists and you can copy it under CC-BY and do whatever you want with it. (No, there is no interactive HTML for reasons we’ll come on to).

I put a LOT of work into the manuscript. The images that you see are mainly interactive (applets, SVG, etc.). Making sure they all work is hard. And, I’ll admit, I was late on the deadline. But I finally got it all together and mailed it off.

Disallowed. It wasn’t *.doc. Of course it wasn’t *.DOC, it was interactive HTML. The Elsevier publication process refused to allow anything except DOC. In a rush, therefore,

I destroyed my work so it could be “published”

I deleted all the applets, SVG, etc. and put an emasculated version into the system and turned to my “day” job – chemical informatics – where I am at least partially in control of my own output.

I have never heard anything more. I got no reviews (I think the editor accepted it asis). I have no idea whether I got proofs. The paper was published along with 7 others some months later. I have never read the other papers, and it would now cost me 320 USD to read them (including mine). There is an editorial (1-2 pages which also costs 40 USD). I have never read it, so I have no idea whether the editor had any comments.

Why have I never read any of these papers? Because this is a non-communication process. If I have to wait months for something to happen I forget. *I* am not going to click on Serials Review masthead every day watching to see whether my paper has got “printed”. So the process guarantees a large degree of obscurity.

Have I had any informal feedback? Someone reading the article and mailing me?

No.

Has anyone read the article? (I include the editor). I have no idea. There are no figures for readership.

Has anyone cited the article?

YES – four people have cited the article! And I don’t have to pay to see the citation metadata :

http://www.scopus.com/results/citedbyresults.url?sort=plf-f&cite=2-s2.0-43149086423&src=s&imp=t&sid=Mt3luOQ49JTT7H5OHiBim3F%3a140&sot=cite&sdt=a&sl=0&origin=inward&txGid=Mt3luOQ49JTT7H5OHiBim3F%3a13

The dereferenced metadata (I am probably breaking copyright) is

1 Moving beyond sharing vs. withholding to understand how scientists share data through large-scale, open access databases

Akmon, D. 2011 ACM International Conference Proceeding Series , pp. 634-635 0

2 Advances in structure elucidation of small molecules using mass spectrometry

Kind, T., Fiehn, O. 2010 Bioanalytical Reviews 2 (1), pp. 23-60 2

3 An introduction to data mining

Apostolakis, J. 2010 Structure and Bonding 134 0

4 Data mining in organic crystallography

Hofmann, D.W.M. 2010 Structure and Bonding 134 0

I cannot read 3 of these (well it would cost ca 70 USD just to see what the authors said), but #2 is Open. Thank you Thomas (I imagine you had to pay to allow me to read it) [Thomas and I know each other well in cyberspace]. It is clear that you have read my article – or enough for your purposes. Thomas writes

that once data and exchange standards are established, no

human interaction is needed anymore to collect spectral

data [525]. The CrystalEye project (http://wwmm.ch.cam.

ac.uk/crystaleye/) shows that the aggregation of crystal

structures can be totally robotized using modern web

technologies. The only requirement is that the spectral data

must be available under open-data licenses (http://www.

opendefinition.org/) [544].

The other three may have read it (two are crystallography publications) or they may simply have copied the reference. It’s interesting (not unusual) to see that the citations are 2 years post publication).

So in summary, the conventional publication system consists of:

- Author expends a great deal of effort to create manuscript

- Publisher “publishes it through an inhuman mechanistic process; no useful feedback is given

- Publisher ensures that no-one can read the work unless…

-

University libraries pay a large sum (probably thousands of dollars/annum each) to allow “free” access to an extremely small number of people (those in rich universities perhaps 0.0001% of the literate world – how many of you can read these articles sitting where you are?)

-

No one actually reads it

In any terms this is dysfunctional – a hacked off author, who has probably upset an academic editor, and who have jointly ensured that the work is read by almost no-one. Can anyone give me a reason why “Serials Review” should not be closed down and something better put in its place? And this goes for zillions of other journals.

Hang on, I’ve forgotten the holy impact factor… (http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/620213/description )

Impact Factor: 0.707

Yup, roughly the square root of a half.

What will my colleagues say?

My academic colleagues (will unfortunately) say that I should not publish in journals with an IF of less than (??) 5.0 (J Cheminfo is about 3). That in itself is an appalling indictment – they should be saying “Open data is an important scholarly topic – you make some good points about A,B,C and I have built on them; You get X, Y wrong and you have completely failed to pay attention to Z.”

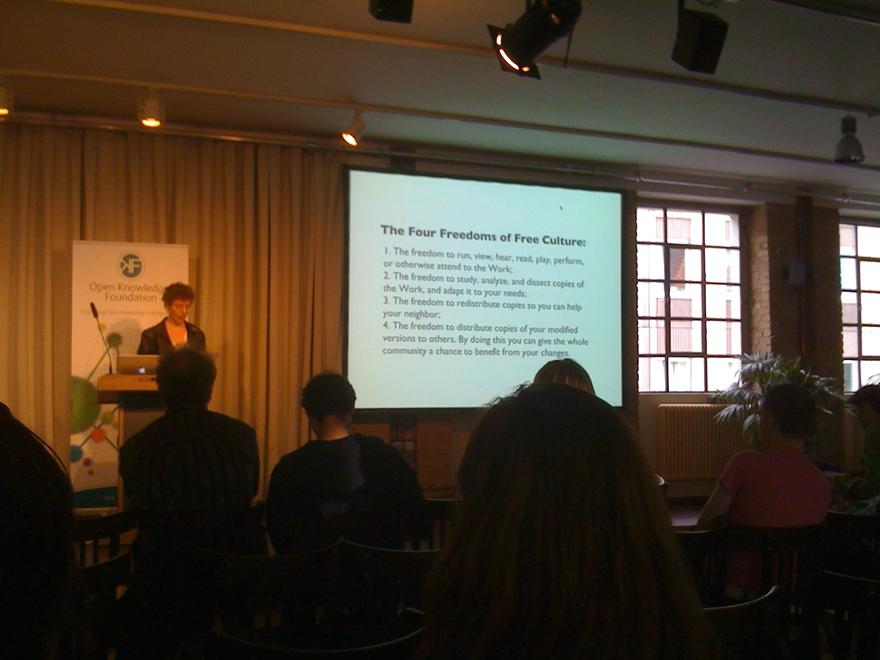

My Open Knowledge and Blue Obelisk colleagues will say – “this is a great start to understanding and defining Open Data”.

And I can point to feedback from the gratis Nature Precedings: (http://precedings.nature.com/documents/1526/version/1 )

This has:

- 11 votes (whatever that means, but it probably means at least 11 people have glanced at the paper)

- A useful and insightful comment

- And cited by 13 (Google) (Scopus was only 4). These are not-self citations.

So from N=1 I conclude:

- Closed access kills scholarly communication

- Conventional publication is dysfunctional

If I had relied on journals like Serials Review to develop the ideas of Open Data we would have got nowhere.

In fact the discussion , the creativity, the formalism has come through creating a Wikipedia page on “Open data” and inviting comment. Google “Open Data” and you’ll find http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_data at the top. Google “Open data in science” (http://www.google.co.uk/search?q=open+data+in+science&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en-GB:official&client=firefox-a ) and the gratis manuscript comes top (The Elsevier article is nowhere to be seen).

As a result of all this open activity I and other have helped to create the Panton Principles (http://pantonprinciples.org/ ). As you will have guessed by now I get no academic credit for this – and my colleagues will regard this as a waste of time for a chemist to be involved in. For me it’s true scholarship , for them it has zero “impact”.

In closing I should make it clear that Open Access in its formal sense is only a small advance. More people can read “it”, but “it” is an outdated, twentieth century object. It’s outlived its time. The value of Wikipedia and Nature Precedings for me is that this has enabled a communal journey. It’s an n<->n communication process rooted in the current century.

Unless “journals” change their nature (I shall explore this and I think the most valuable thing is for them to disappear completely) then the tectonic plates in scholarly publishing will create an earthquake.

So this *is* a scholarly publication – it hasn’t ended up where I intended to go, but it’s a useful first draft. Not quite sure what – perhaps a Panton paper? And if my academic colleagues think it’s a waste, that is their problem and, unfortunately, our problem.

[And yes – I know publishers read this blog. The Marketing director of the RSC rang me up on Friday as a result of my earlier post. So please comment.]

[OH, AND IN CASE THERE IS ANYONE ON THE PLANET WHO DOESN’T KNOW – I DON’T GET PAID A CENT FOR THIS ARTICLE. I DON’T GET REIMBURSEMENT FOR MATERIALS. I DON’T KNOW WHETHER THE EDITOR GETS PAID. THE JOURNAL TAKES ALL THE MONEY FOR “PUBLISHIING MY WORK”].