I have just been reading Peter Suber’s latest SOAN http://www.arl.org/sparc/publications/articles/oanewsletter-oa-and-copyright.shtml (a monthly Open Access news ) and also his interview with Richard Poynder (short version http://poynder.blogspot.com/2011/07/peter-suber-leader-of-leaderless.html contains pointers to full version).

PeterS is, for many of us, the person who has led Open Access to where it is today. His textual discourse is something we should all aspire to. Beautifully and simply wordsmithed, with all the arguments completely and fairly laid out. He has never ranted.

A lunchtime break gives me to opportunity to raise some questions about “Open Access”. Open Access *is* complex and the terminology has sometimes been wayward. It is now converging on two axes Green-Gold and gratis-libre. This classification has taken years to resolve and during that time there has been much confusion. I’m afraid I have to say that several publishers benefit from the confusion and may deliberately promote it by non-standard terminology and poor labelling of products. Indeed if there is one message I would like everyone, especially publishers, to take away from this blogpost its is that precise terminology and clear labelling is essential. If, for example, as an author you pay 3000 USD to create an “Open Access” publication the publisher owes it to you to label it properly and to make it clear what benefits you have received that you may not have got from a non-Open product.

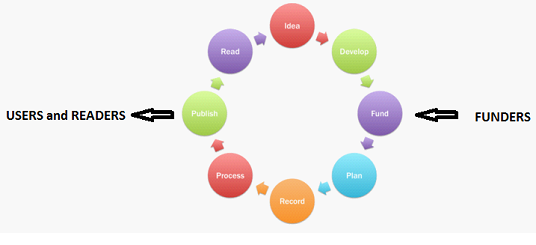

The term “Open Access” by itself is used so variably that all you can determine is that you can see the publication somewhere for free, hopefully for eternity. A responsible publisher should make it clear what the label means. We must also distinguish between visibility and the rights of an arbitrary reader to re-use some or all of the material. I am particularly concerned about rights as I wish to carry out textmining on a massive scale and many types of Open Access forbid this for various reasons. It should therefore be trivially clear on a publication what rights the reader (including a machine) has. This is technically straightforward and only laziness, ignorance or deliberate subterfuge are preventing it.

The right to view and the right to use are , unfortunately, convoluted with when, where and how the document is published, and may depend on versions. This makes the business rules for most publishers different for every other publisher. If you are a full-time information professional (e.g. a librarian or informatician – maybe a funder) then you have time to manage the most important publishers. But for the average author and reader it is unnecessarily confusing. For that reason it can be very hard to get the average person to spend time on the issues. So here goes (if I get this wrong then it shows how complex it is. Wikipedia is, as always, effectively definitive http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_access_%28publishing%29

Colour axis (independent of Gratis/libre and independent of authorside fees)

This is particularly confusing because several colour axes have been in use for different purposes (and may still be so). Moreover colours have no mnemonic value.

Gold applies only to publication through publishers. By submitting a manuscript here the publisher has the responsibility of making the manuscript Open in whatever form and preserving it indefinitely (maybe with a third party). Gold publication may or may not carry author-side fees (for example the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry is a gratis OA publisher with no fees, while BMC, IUCr and PLoS journals have authorside fees. Gold may be gratis or libre. Generally Gold is provided in a single completely Open Access journal (i.e. where all papers are required to be OA). Examples are BMC, PloS and Acta Crystallographica E. A “Gold publisher” is a deprecated term as some publishers (e.g. BMC) have some closed publications.

Green relates to self-archiving, normally of material published in a conventional journal.

Assuming the author has the right, they may or may not choose to self-archive (i.e. by putting it on their website or in their Institutional Repository). The place and number of such archivals *may* be controlled by agreement with the publisher (e.g. you may/mayNot have multiple archivals, use the IR, etc.). There may also be regulations on *what* you archive. These may cover pre-publication (e.g. before peer-review), authors corrected manuscript. It often does not allow archival of the final “publisher’s PDF”. Some universities will help researchers archive their publications. I can personally vouch that self-archival can be a time-consuming business (not a “one-click” process). It may also depend on having a very clear personal record of the timeline of interaction with the publisher.

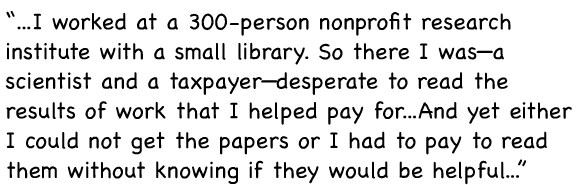

Funders spend much effort negotiating with publishers as to exactly what form of colour is allowed and what type of self-archival.

A special form of (usually Gold) OA is the “hybrid journal“. This is where a single Gold publication appears in the same journal/issue as closed publications. IMO it must be carefully labelled so the reader/user can determine their rights. I see little value in hybrid publications – the publisher gains double revenue and the major benefit (in science) of automatic re-use is probably impossible to determine without a human.

The gratis-libre axis

This applies only to the rights of a reader and the terms are descended from Richard Stallman and others. The terms “Free” and “Open” should be avoided when taking about this axis. Gratis is “free as in beer” and libre is “free as in speech”. Gratis grants no rights, other than to read; libre grants significant rights. The fundamental Open Access declarations (Budapest, berlin, Bethesda) defined open Access in “libre”-oriented prose. Unfortunately much of that clarity has become muddied, and is only now refocussing. Libre must, IMO, be accompanied by a precise definition of the rights of the re-user. I would urge these to be compliant with the Open Definition (http://www.opendefinition.org/ )

“A piece of content or data is open if anyone is free to use, reuse, and redistribute it — subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and share-alike.”.

I reiterate – Gold/Green and Gratis/Libre are formally independent.

I was surprised to see from Peter Suber’s interview that a large proportion of Gold OA was not libre. Peter often measures by journals, whereas I measure by articles, especially in STM. Since most Gold OA is now likely to come from funder mandates it would worry me a lot if they were only buying Gratis for their money.

Why is libre so important? What do you get for your money? (assuming you pay and this isn’t donated by the journal).

- You get certainty for your reader (assuming the libre rights are well defined). You should certainly get a clear licence or contract for your payment.

- Assuming the libre is OpenDefinition compliant your reader can re-use the material for almost anything. This includes teaching, book chapters, slide shows, movies, databases, textmining, data mining.

- You SHOULD get a clear indication on/in the document itself what the (a) authorship is and (b) the reader’s rights

If you get an undefined gratis document you cannot assume ANY of these things by default. To add rights to a self-archived document is often problematic. You cannot make assumptions that a given document carries rights unless it actually carries them. Institutional Repositories compound this, often by failing to state rights, failing to add rights to documents or even worse (as Cambridge and I suspect many others do) adding the blanket disclaimer:

Items in DSpace are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

The reiterates the default copyright position that:

Readers have no rights by default

“fair use” does not apply in the UK. DSpace does not know the author’s date of death so can never assert that an item is formally out of copyright. Therefore by default:

Unless the author/self-archivist makes a special effort, the reader has no rights of use over the deposited item

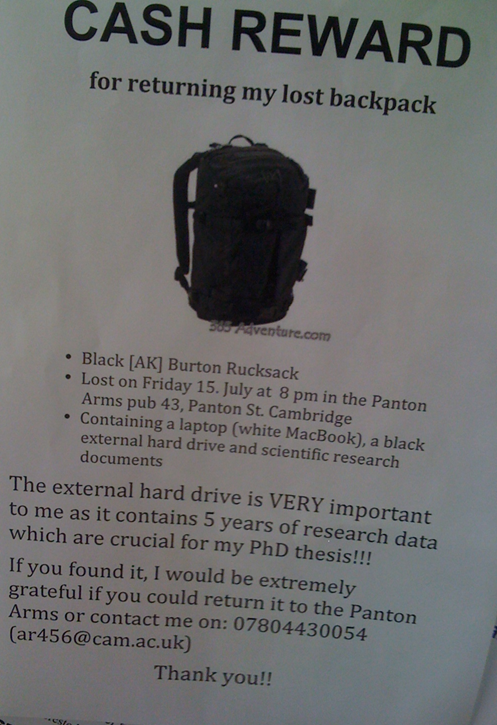

Modern e-science requires documents over which the reader/user has rights of re-use, which is why Green self-archiving is of little value to high-volume information analysts. Moreover the author has not only to indicate that the item is libre, they also have to do it in a way where the information is easily discovered.

It is incredibly difficult to discover libre Open Access items unless they are published under the Gold system in a “Gold journal” – i.e. where every paper is guaranteed to be libre. Here are some simple questions, which despite the large amount of resource poured into the system I cannot even start to answer:

I believe there are publishers out there who are trying to be constructive players in the Open Access market , i.e. giving the authors/funders value for their libre-fee. (I suspect there are some who are dragging their feet and giving as little value as possible for large fees). So constructive publishers, here is a check list:

- Are all your libre publications labelled, both on the splash page and in the text itself with the readers’ rights? (A simple statement of CC-BY accomplishes this)

- If you run hybrid journals is it easily possible to search for the libre content? Both by human and machine. This is not simply provided by a label saying “libre” but is a systematic exposition – effectively a separate TOC for libre content.

After all the author/funder can be paying a lot for a hybrid publication – all parties should regard this as an honourable transaction, not some back-street bargain.

And for repository managers:

- Do all items carry explicit rights? Do you make it easy for these to be added (DSpace does not)

- Does a reader/machine have an index of all your libre content?

- Are your licences OKD-compliant and machine-readable

And for funders;

- Are you insisting on full libre for your fee payments

- Are you highlighting the value to society by creating indexes of the libre documents you have sponsored? (yes I know authors don’t comply always!)

- Are you advocating the value of re-use rather than just visibility and showing it is value for money?