I have got useful feedback from my last post about design of repositories and it raises some serious issues which will be important in future discussions. [I should say that I get very little feedback, which is a pity as I am actually trying to be constructive. Not in the sense of pretending everything is fine and we need incremental growth. But telling it how it is, and how it needs to be.]

There are many motivations for repositories, and I will touch on them later. They range from managing the institution’s business processes to altruistic storage of important digital objects (for a wide variety of processes).

It is impossible for all of these to be properly served by a single repository management and a single repository management system. In the world outside academia we build repositories in response to need (often our own). Both the design of the project and the design of the software is geared towards specific goals.

Repositories are hard. [I base this on Carole Goble’s announcement some year ago that “workflows are hard”, after we had burnt six months trying to get Taverna to do something it wasn’t designed to do (chemistry) though everyone thought it could]. I only know DSpace (please don’t tell me that ePrints and Fedora are ipso facto wonderful and the solution to my problems – they aren’t.] Most attempts to design a repository system will either serve a small section of the community, or not serve anything. DSpace fall into the former. It’s basically a twentieth-century approach to managing electronic library objects. It’s heavy on formal metadata, non-existent on community, feedback, etc. If you don’t have these and many other things in the current era then success is due to political or financial power, not excellence of design.

History – about 5 years ago I bought into the idea that DSpace@cam was for sharing useful digital objects with the rest of the world – and preserving them for a year or three. I and colleagues had run 750,000 computational chemistry jobs (based on molecules from the National Cancer Institute, US) and it took us months. We thought it would be useful for others to be spared the effort of repeating that. (We had published that in a closed journal – partly due to circumstances). BTW there are probably > 100 million comp chem jobs run each year and NONE of them are shared. We wanted to change that culture. So Jim Downing wrote a system to put them all into DSpace. We weren’t worried about the REF. We weren’t worried about promoting Green Open Access. We weren’t interested in promoting the reputation of the university (although if it helps, fine). We wanted to store the stuff, 175000 calculations, somewhere.

So Jim did this. It’s not a particularly clean collection because there are duplicates and crashes. We have subsequently built tools which help to minimize this problem. That’s HARD and tedious. The collection suffers from several major flaws, mainly due to DSpace software. If I implicitly criticize people, they are generic criticisms of IRs – not specific to Cambridge.

-

It is impossible to search the collection for anything other than crafted metadata – no chemistry or numeric values. But that is what chemists want to do. The titles are meaningless. The authors are meaningless. Most of the traditional metadata is non-existent.

-

It is impossible to iterate over the collection. It is really important that you understand this, because if you do not, your repository is largely useless for science and technology objects. Someone mailed me and asked if I could let him have all the objects in to collection. A very reasonable request. I was delighted to help. Except I couldn’t. Not didn’t want to. Couldn’t. For at least 2 reasons: (a) there was no single list of all the entries and (b) even if there was it wouldn’t retrieve the data, but only the HTML metadata. That’s because DSpace is basically a metadata repository assuming that searches are by humans and for humans to click on the links. Yes, it has OAI-PMH but that’s not going to help me find my molecules. (People keep telling me that the repositories have OAI-PMH and I should use it. How? By writing a repository crawler?).

-

There are no download statistics visible to depositors or users. (See below).

-

There is no way for humans to leave annotations. Such as “Liked this”, “this entry is rubbish” (several are), “are you going to be producing more?”, “I’d like to use them for …”.

-

There is no way for me to help innovate the system other than by moaning on this blog. Which I don’t actually enjoy. There is a wealth of young talent waiting to build and modify information systems and the opportunities are limited because there is a presumed architecture of humans depositing e-objects and humans searching and browsing e-objects.

So to the comments:

Steve Hitchcock [A well known guru from Southampton] says: August 17, 2011 at 9:58 am

Steve Hitchcock [A well known guru from Southampton] says: August 17, 2011 at 9:58 am

>> Peter, It pains me to say it, but you have some valid criticisms of institutional repositories. As a passionate supporter of IRs my view is that IRs broadly exhibiting the problems you identify lack leadership, that is, institutional leadership (it’s in the term, *I*R). As a result many repository managers are left thrashing around to find a purpose and identity for the repository. And yet. If you look closely, you will find exemplary IRs.

PMR: I am reasonably appreciative of the Soton commitment and the amount of content, but I’m not aware of much else. You will have to be specific; I shouldn’t have to look closely – it should be self-evident

>>These may be typical open access IRs, or untypical but with a clear focus and implementation to match. From experience there are repository teams taking exemplary approaches, but it is not apparent in the resulting repository, yet. They will be rewarded if the institution recognises and backs their efforts.

PMR: This is rather close to vapourware. Five years of non-progress for my requirements have made me take a different tack.

>>The wider repository community might be too slow to recognise, promote and emulate its best, and not always clear on the importance of their mission. Let’s be clear, you recognise the importance of the mission, ultimately the progress of science and wider academic endeavour by correct and proper management and access to all of its critical (now) digital outputs,

PMR: Yes, I do – I am passionate about it.

>> yet your response to current perceived problems is to look for instant solutions without joining it all up.

PMR: They aren’t instant, but they happen within months rather than a decade. And they are solutions. Our extended group has developed Crystaleye (250,000 entries), Chempound/Quixote (thanks to JISC funding) with ca. 40,000 combined crystal and compchem entries, BibSoup (20 million bibliographic records), etc. These all took less than a year before deployment. Yes, they are raw, and yes some of the architecture may later be replaced but they are evolving systems.

>>IRs can offer a joined-up approach to the mission. That is why they were conceived, and we too often and too easily lose sight of that. The way forward is to highlight and learn from the best IRs. That is the way to fix these problems, rather than abandon them.. I

PMR: Unless you give specifics this is no use. I WANT to join up IRs. I have made a practical suggestion on this Blog – no interest. I have asked how we do federated search. No replies. I want to retrieve all UK theses. I can’t (I am told “you can do this through eTHOS” – how?)

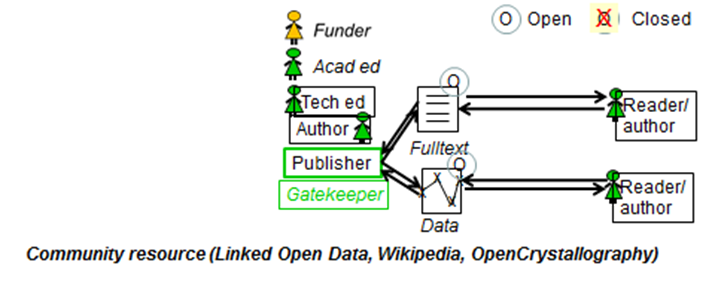

PMR: I could believe in federated repositories if I saw some examples. They won’t be easy to scale – we have seen this in RDF/LOD. But I actually suspect that very few people actually want to federate repositories – why should they when part of the purpose of a repo is to compete against other institutions? Federation is most effective when the identity of the components is irrelevant

Chris Rusbridge [ex-director of the Digital Curation Centre] says: August 17, 2011 at 10:03 am (Edit)

Chris Rusbridge [ex-director of the Digital Curation Centre] says: August 17, 2011 at 10:03 am (Edit)

CR >>Peter, my sincere apologies for not letting you know this before, but you vastly under-estimate the usage of the WWMM collection. The report I wrote on DSpace @ Cambridge belongs to the University Library, but I’m sure they will not mind if I quote one paragraph to you:

“There have been concerns that the huge WWMM collection might be essentially unused. Because of the Handle-like structure of identifiers, it is not easy to count accesses to all the items in a collection. However, thanks to sterling work by the DSpace team, they were able to determine that accesses to the WWMM collection represent approximately 12.5% of total accesses over the 15-month period available. This is a respectably high usage rate, that justifies keeping the collection, and comes despite the fact that 104,000 of the 175,000 items in the collection received no accesses at all during that period (a classic long tail effect).”

One in every eight accesses to the repository was to that collection.

Thanks, Chris.

Firstly, I had no knowledge of this whatsoever and it re-emphasizes that repositories are useless to depositors unless there is feedback. So I have millions of downloads of my entries (do the power law sums). Where from, Machines? Humans? What for? What are the popular molecules?

I should thank the DSpace team for their work although I had no idea it was going on.

If I had known I would have made some suggestions as to improvement. An obvious one would be a simple feedback button “found this useful”. A chance to mail me. How many potential collaborators might I have had if I had known? (A note of caution – we have had >300,000 downloads of our Chem4Word software and not a single communication other from those who have technical problems. So I don’t expect much.

I am now involved in setting up a new generation of molecular repository – Quixote. This will allow the questions above to be answered, and for people to innovate. This is not vapourware – it exists and is being cloned.

So I am grateful to the University for supporting this resource. But it actually make much more sense for SOME university to support Quixote. It will have far more use than PMRmolecules@Dspace. Because people can deposit their own work. For their own purposes.

So – once again a question to readers…

Is anyone interested in supporting a world repository for computational chemistry?

Or are universities forever tied to only looking after their own? In which case expect to see me and others do it outside the IR system.

RSN.

Steve Hitchcock [A well known guru from Southampton] says:

Steve Hitchcock [A well known guru from Southampton] says:  Chris Rusbridge [ex-director of the Digital Curation Centre] says:

Chris Rusbridge [ex-director of the Digital Curation Centre] says: