I’ve been invited to a COST meeting in Porto (PT) on Monday. COST is “an intergovernmental framework for European cooperation “ and I’m a member of a working group on automating computational chemistry (D37). But this is different – HLA-NET MC-WG is “A European network of the HLA diversity for histocompatibility, clinical transplantation, epidemiology and population genetics.” They are interested in how they share data (and materials) through an Open process.I didn’t need to know anything about sharing materials, privacy, etc. [BTW I may use “data” as a singular noun deliberately].

So last Tuesday we had a visit from Cameron Neylon (who incidentally gave a brilliant talk on Open Science , blogged by Nico Adams) and our group went to the Panton Arms (pub) for lunch. I took the opportunity to get Rufus Pollock of the Open Knowledge Foundation to discuss and clarify what our common stance is on Open Data. Cameron has blogged very comprehensively and usefully on the meeting. Rufus has also summarized views from Open Data Commons.

The critical thing to realise is that Open Scientific Data is not Open Software nor Open Content. It may sound arrogant but it can be difficult for a non-scientist to realise that is is different from maps, from Shakespeare, from photography, from government publications, from cricket scores. Scientists by default collect data, or calculate it, to justify their conclusions to prove they have done the work, to allow others to repeat the work.

It should be free, as in air.

They expect others to use it, without their permission. This could be to provde the original ideas right, or to prove them wrong. It could be to mine the data for ideas the original scientists missed. No scientist likes being proved wrong, or having someone else find ideas that they have missed. But it’s a central part of science. A scientist who says “you can’t use my published data” has no credibility today.

That’s not to say some scientists don’t try to hold their data back and mine the maximum from it before publishing. But it is becoming increasingly required – by funders, by universities (in theses) and by some publishers – that the data justifying a publication should be “published” in some way at the time of article publication. And by default there should be no restrictions on copying, re-use , republishing for whatever purpose and by whomever. I may not like it if my data is used to make weapons, or that a commercial organisation republishes it for money. But that is the implied contract I make by being a scientist. If I don’t like weapons derived from science there are other ways I can make my views known other than by adding restrictions – and at times I have.

To summarize. Data itself must be completely free. The question is how to ensure that it is.

The Open Science and Open Knowledge community has been discussing this for about 2 years. We seem to be agreed that legal tools are counterproductive, and that moderation is best applied by the community. This is represented by Community Norms – agreed practices that cause severe disapproval and possibly action when broken.

Our current crisis in Britain illustrates this. Huge numbers of Members of Parliament have been fiddling their expenses. They’ve been spending taxpayers’ money on cleaning their castle moats, buying second homes, antique rugs and so on. Huge amounts. This is, apparently, within the parliamentary guide lines.

But it is against the court of public opinion. It violates our Community Norms. The defence that it is “within the rules” illustrates the futility of the rules.

And it is incredibly difficult to draft good rules. So we’ve decided not to try to use the standard tools of copyright or licences.

For us Data are born Open. The question is how to state that. The simplest way is just to add the OKF’s “Open Data” button to the data. That’s a statement of intent. It says “you can do whatever you like with this data without asking my permission.” In many cases I think that is adequate.

However the community has also investigated the legal aspect and to provide a formal means of stating this in legal terms. This isn’t easy but the two approaches – Public Domain Dedication and Licence (PDDL) and Creative Commons CC0 – are roughly equivalent. I hope it’s useful to say that PPDL comes out of an Open Knowledge philosphy and deals with collections and other non-scientific content, whereas CC0 springs more directly fro

m science. And it IS complex – I am meant to be an expert and I still find the details difficult. Here’s the CC0 FAQ:

How is CC0 different from the Public Domain Dedication and License (“PDDL”) published by Open Data Commons?

The PDDL is intended only for use with databases and the data they contain. CC0 may be used for any type of content protected by copyright, such as journal articles, educational materials, books, music, and art, as well as databases and data. And just like our licenses, CC0 has the added benefit of being expressed in three ways: through a human-readable deed (a plain-language summary of CC0), the legal code, and digital code. The digital code is a machine-readable translation of CC0 that helps search engines and other applications identify CC0 works by their terms of use.

This was the background when we tried to achieve a common view in the Panton. I’ll let Cameron take it from here:

The appropriate way to license published scientific data is an argument that has now been rolling on for some time. Broadly speaking the argument has devolved into two camps. Firstly those who have a belief in the value of share-alike or copyleft provisions of GPL and similar licenses. Many of these people come from an Open Source Software or Open Content background. The primary concern of this group is spreading the message and use of Open Content and to prevent “freeloaders” from being able to use Open material and not contribute back to the open community. A presumption in this view is that a license is a good, or at least acceptable, way of achieving both these goals. Also included here are those who think that it is important to allow people the freedom to address their concerns through copyleft approaches. I think it is fair to characterize Rufus as falling into this latter group.

On the other side are those, including myself, who are concerned more centrally with enabling re-use and re-purposing of data as far as is possible. Most of us are scientists of one sort or another and not programmers per se. We don’t tend to be concerned about freeloading (or in some cases welcome it as effective re-use). Another common characteristic is that we have been prevented from being able to make our own content as free as we would like due to copyleft provisions. I prefer to make all my content CC-BY (or cc0 where possible). I am frequently limited in my ability to do this by the wish to incorporate CC-BY-SA or GFDL material. We are deeply worried by the potential for licensing to make it harder to re-use and re-mix disparate sets of data and content into new digital objects. There is a sense amongst this group that “data is different” to other types of content, particulary in its diversity of types and re-uses. More generally there is the concern that anything that “smells of lawyers”, like something called a “license”, will have scientists running screaming in the opposite direction as they try to avoid any contact with their local administration and legal teams.

PMR: I am completely aligned with Cameron. The added precision of legality is seriously outweighed by its difficulty and downstream problems. Cameron again:

What I think was productive about the discussion on Tuesday is that we focused on what we could agree on with the aim of seeing whether it was possible to find a common position statement on the limited area of best practice for the publication of data that arises from public science. I believe such a statement is important because there is a window of opportunity to influence funder positions. Many funders are adopting data sharing policies but most refer to “following best practice” and that best practice is thin on the ground in most areas. With funders wielding the ultimate potential stick there is great potential to bootstrap good practice by providing clear guidance and tools to make it easy for researchers to deliver on their obligations. Funders in turn will likely adopt this best practice as policy if it is widely accepted by their research communities.

So we agreed on the following (I think – anyone should feel free to correct me of course!):

1. A simple statement is required along the forms of “best practice in data publishing is to apply protocol X”. Not a broad selection of licenses with different effects, not a complex statement about what the options are, but “best practice is X”.

2. The purpose of publishing public scientific data and collections of data, whether in the form of a paper, a patent, data publication, or deposition to a database, is to enable re-use and re-purposing of that data. Non-commercial terms prevent this in an unpredictable and unhelpful way. Share-alike and copyleft provisions have the potential to do the same under some circumstances.

3. The scientific research community is governed by strong community norms, particularly with respect to attribution. If we could successfully expand these to include share-alike approaches as a community expectation that would obviate many concerns that people attempt to address via licensing.

4. Explicit statements of the status of data are required and we need effective technical and legal infrastructure to make this easy for researchers.

So in aggregate I think we agreed a statement similar to the following:

“Where a decision has been taken to publish data deriving from public science research, best practice to enable the re-use and re-purposing of that data, is to place it explicitly in the public domain via {one of a small set of protocols e.g. cc0 or PDDL}.”

PMR: agreed. The biggest danger is NOT making the assertion that the data is Open. There may be second-order problems from CC0 or PPDL but they are nothing compared to the uncertainty of NOT making this simple assertion. Do not try to be clever and use SA, NC or other

restricted licenses. Simply state the data are Open. Cameron finishes:

The advantage of this statement is that it focuses purely on what should be done once a decision to publish has been made, leaving the issue of what should be published to a separate policy statement. This also sidesteps issues of which data should not be made public. It focuses on data generated by public science, narrowing the field to the space in which there is a moral obligation to make such data available to the public that fund it. By describing this as best practice it also allows deviations that may, for whatever reason, be justified by specific people in specific circumstances. Ultimately the community, referees, and funders will be the judge of those justifications. The BBSRC data sharing policy states for instance:

BBSRC expects research data generated as a result of BBSRC support to be made available…no later than the release through publication…in-line with established best practice in the field [CN – my emphasis]…

The key point for me that came out of the discussion is perhaps that we can’t and won’t agree on a general solution for data but that we can articulate best practice in specific domains. I think we have agreed that for the specific domain of published data from public science there is a way forward. If this is the case then it is a very useful step forward.

PMR: completely agreed. Now there are some important actions:

-

get funders, universities and well-intentioned publishers to agreed on this approach, with appropriate modifications. It should be sufficient to see the Open Data button to know that the data are free for re-use.

-

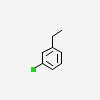

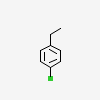

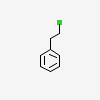

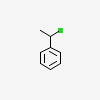

Assert that Data covers images and tables and other ways of representing data. It is archaic and bizarre that data presented as an image are copyrightable. We must change this – it’s far more important than the second order problems of PPDL/CC0

-

Cameron has called, this “A breakthrough on data licensing for public science”. If others agree let’s call it the “Panton Principles” of Open Data.