In the previous post (/pmr/2013/05/23/sepublica-how-semantics-can-empower-us-scholrev-scholpub-btpdf2/) I outlined some of the reasons why semantics are so important. Here I want to show what we have to do (and again stick with me – although you might disagree with my stance).

The absolute essentials are:

- We have to be a community.

- We have to identify things that can be described and on which we are prepared to agree.

- We have to describe them

- We have to name them

- We have to be able to find them (addressing)

Here Lewis Carroll, a master of semantics shows the basics

And she went on planning to herself how she would manage it. `They must go by the carrier,’ she thought; `and how funny it’ll seem, sending presents to one’s own feet! And how odd the directions will look!

ALICE’S RIGHT FOOT, ESQ.

HEARTHRUG,

NEAR THE FENDER,

(WITH ALICE’S LOVE).

Oh dear, what nonsense I’m talking!’

Alice identifies her foot as a foot, and makes gives it a unique identifier RIGHT FOOT. The address consists of another unique identifier (HEARTHRUG) and annotates it (NEAR THE FENDER). There’s something fundamental about this – (How many children have annotated their books with “Jane Doe, 123 Some Road, This Town, That City, Country, Continent, Earth, Solar System, Universe?). Hierarchies seem fundamental to humans. Anything else is much more difficult. (Peter Buneman and I have been bouncing this idea about). I am sure we have to use hierarchies to promote these ideas to newcomers.

Things get unique identifiers. They can be at different levels. Single instances such as Alice’s left foot.

But there are also whole classes – the class of left feet. I have a left foot. It’s distinct from Alice’s. And we need unique names for these classes, such as “left foot“. Generally all humans have one (but see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Man_with_Two_Left_Feet ). And we can start making rules, see http://human-phenotype-ontology.org/contao/index.php/hpo_docu.html.

At the moment, all relationships in the Human Phenotype Ontology are is_a relationships, i.e. a simple class-subclass relationships. For instance, Abnormality of the feet

is_a

Abnormality of the lower limbs. The relationships are transitive, meaning that they are inherited up all paths to the root. For instance,

Abnormality of the lower limbs is_a

Abnormality of the extremities, and thus Abnormality of the feet also is Abnormality of the extremities.

We see a terminology appearing. Some would call this an ontology, others would refute this. I tend to use the concept of “dictionary” fuzzed across language and computability.

This is where the difficulties start. One the one hand this is very valuable – if a disease affects the extremities, then it might affect the left foot. But it’s also where people’s eyes glaze over. Ontology language is formal and does not come naturally to many of us. And when it’s applied like a syllogism:

- All men are mortal

- Socrates is a man

- Therefore Socrates is mortal

Many people think – so what? – we knew that already. On the other hand it’s quite difficult to translate this into machine language (even after realising that “men” is mans (the plural). The symbology is frightening (with upside down A’s and backwards E’s). Here are fundamental concepts in a type system: http://stackoverflow.com/questions/12532552/what-part-of-milner-hindley-do-you-not-understand :

The discussion on Stack Overflow includes:

- “Actually, HM is surprisingly simple–far simpler than I thought it would be. That’s one of the reasons it’s so magical”

-

“The 6 rules are very easy. Var rule is rather trivial rule – it says that if type for identifier is already present in your type environment, then to infer the type you just take it from the environment as is. PMR is still struggling with the explanation

- This syntax, while it may look complicated, is actually fairly simple. The basic idea comes from logic: the whole expression is an implication with the top half being the assumptions and the bottom half being the result. That is, if you know that the top expressions are true, you can conclude that the bottom expressions are true as well.

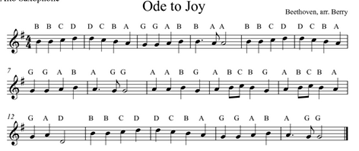

The problem is language and symbology. If you haven’t been trained in language it’s often impenetrable. For example music. If you haven’t been trained in it, it makes little sense and takes us a considerable time to learn:

So if we want to get a lot of people involved we have to be very careful about exposing newcomers to formal semantics. I avoid words like ontology, quantifier, predicate, disjunction, because people already have to be convinced they are worth learning.

Humans want to learn music not because they’ve seen written music but because they’ve heard music. Similarly we have to sell semantics by what it does, rather than what it is. And we cannot show what it does without building systems, any more than we are motivated to learn about pianos until we have seen and heard one.

The problem is that it’s a lot of effort to build a semantic system and that there is not necessarily a clear reward. The initial work, as always, was in computer science which showed – on paper – what could be possible but didn’t leave anything that ordinary people can pick up on. This is very common – before the WWW was a whole decade or more of publications in “hypermedia” but much of this was only read by people working in the field. And often the major reason for working in a new field is to get academic publications, not to create something useful to the world. There often seems to be a lag of twenty years and indeed that’s happening in semantics.

So it’s very difficult to get public funding to build something that’s useful and works. One effect is that the systems are built by companies. That’s not necessarily a bad thing – railways and telephones came from private enterprise. But there are problems with the digital age and we see this with modern phones – they can become monopolies which constrain our freedom. We buy them to communicate but we didn’t buy them to report our location to unknown vested interests.

And semantics have the same problem. The people who control our semantics will control our lives. Because semantics constrain the formal language we use and that may constrain the natural language. We humans may not yet be in danger of Orwell’s Newspeak but our machines will be. And therefore we have to assert rights to have say over our machines’ semantics.

That raises the other problem – semantic Babel. If everyone creates their own semantics no-one can talk (we already see this with phone apps). I live in the semantic Babel of machine-chemistry – every company creates a different approach. Result – chemistry is 20 years behind bioscience where there is a communal vision of interoperable semantics.

So I think the major task for SePublica is to devise a strategy for bottom-up Open semantics. That’s what Gene Ontology did for bioscience. We need to identify the common tools and the common sources of semantic material. And it will be slow – it took crystallography 15 years to create their dictionaries and system and although we are speeding up we’ll need several years even when the community is well inclined. (That’s what we are starting to do in computational chemistry – the easiest semantic area of any discipline). It has to be Open, and we have to convince important players (stakeholders) that it matters to them. Each area will be different. But here are some components that are likely to be common to almost all fields:

- Tools for creating and maintaining dictionaries

- Ways to extract information from raw sources (articles, papers, etc.) – that’s why we are Jailbreaking the PDF.

- Getting authorities involved (but this is increasingly hard as the learned societies are often our problem , not the solution)

- Tools to build and encourage communities

- Demonstrators and evangelists

- Stores for our semantic resources

- Working with funders

We won’t get all of that done at SePublica. But we can make a lot of progress.